I love West Bay Opera and was thrilled to find that their production of Turandot by Puccini more than held its own in comparison to the Met HD’s performance.

Last July, when I saw the MetHD performance of Puccini’s Turandot for the 3rd time in 8 months, I wrote, (click here if you’d like to see the full review), “This time I came prepared to swallow the stupidity whole and really give in to the story, the music, and the production. I accepted not only the unrealistic fact of ‘Love-at-first-sight’, but also the fact that it was a form of enchantment – once he saw Turandot’s sneering face, Calé f was a gone goose and was no longer responsible for his actions.”

When I walked into the 400-seat Lucie Stern Theatre in Palo Alto Friday night, February 18, 2011 for the opening night performance, I knew that I had tamed the logical part of my brain and would refer only to the artistic part in evaluating West Bay Opera’s production.

I love West Bay Opera. I want every one of their performances to be an artistic and financial success. But was this possible? How could a small opera company in a small theater with a limited budget compete with the Met version still in my mind?

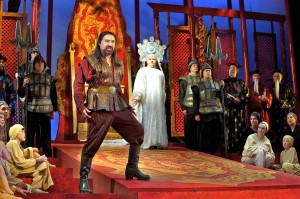

Well, I don’t know how they did it, but they did it. Right from the start. Set Designer Peter Crompton’s opening set was exactly right for Lucie Stern’s stage and exactly right for Puccini’s opera. I’ve seen almost every West Bay Opera production for the past 17 years, and several years ago I helped paint some of the scenery under Peter’s direction. I’ll swear he made that stage seem half again as large as I know it really is.

In fact, kudos to the entire Artistic Direction & Design team, starting with WBO General Director and Conductor (JosÉ Luis Moscovich), and including the Director (David Cox), Set Designer (Peter Crompton), Costume Designer (Callie Floor), Lighting Designer (Robert Ted Anderson), and Sound Designer (Tod Nixon). Collectively they put together a production that perfectly matched the requirements of the opera Turandot with the capabilities of the Theater.

. . . . I started writing this review when I got home Friday night. It’s now Sunday evening and I have just seen Turandot again. The second performance was even better than the first so I will just go on showering praises from where I left off yesterday.

The singing was fantastic. Alexandra LoBianco as Turandot could have filled a much larger hall than Lucie Stern’s, and David Gustafson as Calé f was a perfect match. When they sang a duet, Maestro Moscovich could let the enlarged orchestra go all out – and the singers still dominated. The hall was so full of music that it seemed to penetrate my very bones.

Liisa Dé¡vila as Lié¹ charmed rather than dominated. Her lovely clear soprano was spell-binding in both her arias. I thought her rendition of Signore, ascolta was the musical high point of the opera – I liked it even more than Calé f’s famous Nessun Dorma! in Act III.

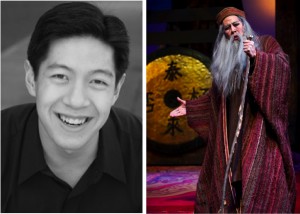

As you can see, Adam Paul Lau looks a mite young to be playing Timur. And indeed, his magnificent deep bass voice could hardly have issued from an eighty-and-counting year old man – but that’s operatic license. His slow creaking motions defined his age just as much as that magnificent beard.

The three ministers, Michael Mendelsohn, Michael Desnoyers. and Emmanuel Franco as Pong, Pang, and Ping were delightful, both individually and collectively. Like the porter in Macbeth they provide a bit of comic relief from the tension in Acts I and III but their charming trio which constitutes Act II, Scene 1 is a lovely mixture of comedy and nostalgia. Let me describe it.

The curtain rises to reveal only another great Peter Crompton set, but Ping, Pang, and Pong soon bustle on each followed by a dead-pan slave carrying a medium-height stool. The ministers are describing their work, work, work of preparing for a celebration without knowing if it will celebrate a beheading or a wedding. They sing solo lines, duet lines, and trio lines to staccato oriental-like accompaniment (Puccini’s idea of legendary Chinese music) and their movements and stoppages are as intricate as their harmonies. While all this is going on, each slave’s job is to move the stool around so that it is directly behind his master. Sure enough, whenever a minister decides to rest for an instant, he sits back without looking, confident that his stool will be there to support him.

After a bit they halt all this frenzied activity and start reminiscing about how much happier each would be back at his own lovely house with its “little blue lake,” “forest”, etc. instead of here in the rat race of Peking. During most of this extended interlude there is only limited motion by the singers and none by the stools. I talked with Michael Mendelsohn after the opening night performance and he said, “This is my favorite scene in all of opera. I regard the opportunity of singing it as a gift – a pure gift.”

Suddenly they hear activity noises off-stage, stop dreaming, and get back to work, i.e. bustling and singing about their tough jobs and being followed by their stools; then they all trot off and we get back to the serious business of the three riddles.

That scene illustrates David Cox’s skill as a director. The stools were his idea. Puccini’s annotations to the score don’t say, “Stools”; they don’t say, “No stools”. During the comic parts of the scene the stools are in perfect harmony with the music and with the story. They enhance the comedy but do not dominate it. And when the mood turns sentimental, they quietly fade into the background.

And don’t forget the chorus. The largest chorus WBO has ever used: 30 as opposed to the usual 24. Plus a children’s chorus of 9. By the way, they are all unpaid volunteers. I talked to a couple of them at the reception and they agreed that this was one of the most difficult operas they’ve ever done – and one of the most rewarding. The music itself wasn’t difficult, but there was more of it, they were on and off stage more times, some of the blocking was quite complex, and it had to be even more precise than usual because of so many people on such a small stage. It all went off beautifully. Congratulations!

I can’t end this review without commenting on Turandot’s great melt-down after Calé f’s powerful kiss. Before that kiss, Alexandra LoBianco played the part of Turandot perfectly. Her scornful sneer for the weak and bumbling princes who quailed before her questions was devastating. The brief doubt that crossed her mind when Calé f correctly answered her first two questions was perfectly expressed by her face and her body language, as was the return to confidence and the sneer as she reassured herself that he’d surely flunk the next question. What made it particularly impressive for me was my opportunity to talk briefly with her at the reception after opening night and to see her at the talk-back session after the Sunday matinee. The bubbly, warm, happy, personality of Alexandra, the person, was such a contrast to the ice-cold sneer of Turandot, the princess!

How can one kiss transform that sneer into an adoring look of hero worship as she gazes at Calé f? Puccini says it does, but a small laugh ran through both audiences at the absurdity of it all. At the talk-back, LoBianco explained it by saying that Turandot’s ice-cold personality was a shield and that beneath it was a scared little girl who was obsessed with the fate of her distant ancestress. I can see how with that interpretation Calé f’s forcible but gentle kiss could bring a sudden recognition that not all men were like that brutal rapist – but without benefit of off-stage interpretation, how do you get it all across to an audience? At the talk-back, one audience member remarked, “It’s my belief that Puccini decided to die before finishing Turandot because he couldn’t figure out a satisfactory way to arrive at the ending he wanted.” My only solution is that you have to see it at least twice and think a lot about it in between. Or go ahead and laugh – after all, it is leading up to a happy ending.

For me, the emotional climax comes before the ending of the opera, right after Lié¹ took her own life. A group from the chorus have picked up her body and are carrying it reverently off stage. Timur takes her lifeless hand in his and sings, “Let me hold your hand once more, gentle Lié¹, and take this last walk with you.” That’s all highly emotional and all specified in the score – every director must include it. But David Cox raises the emotional level. Before the procession has left the stage, a little girl from the children’s chorus rises up silently, with concentrated solemnity, walks up to Timur, gently takes his hand from Lié¹’s, places it on her own shoulder, and leads him off.

Not only has Lié¹’s sacrifice saved Calé f’s life, helped cure Turandot’s obsession, and (presumably) led to an heir to the throne of Turan, but it has inspired and ennobled this little peasant girl. One does not have to believe in literal transmigration to believe that Lié¹ is not really dead – she lives on in this tiny anonymous peasant walking off stage with Timur’s hand on her shoulder.

Thank you, David, for adding this new and deeper significance to Puccini’s magnificent opera. I am sure he would have approved.

Finally, a bit of good news/bad news. The good news is, the opera will be performed twice more this coming weekend on Saturday, February 26 and a matinee the next day. The bad news is, both performances are already sold out. And the moral is, don’t take a chance. Buy your ticket now for West Bay Opera’s final production of the season, a double bill of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas with De Falla’s La Vida Breve on May 20, 22, 28, 29

| West Bay Opera | 221 Lambert Avenue |

| Lucie Stern Theatre | 1305 Middlefield Road |

| Palo Alto, CA 94306 | 650.424.9999 |

Color-Action Photos by Steve DiBartolomeo; black & white head shots courtesy West Bay Opera

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on February 21, 2011.