It was an unlikely combination. A beautifully tragic play by a 19th century Frenchman, loosely based on a real person from 200-some years before; an unsuccessful operetta by an American composer who had emigrated from Germany in the 19th century; a brand-new libretto by a living American whom I’d never heard of; production by a strictly volunteer opera company whose previous productions this season had not impressed me; a conductor and singers who were all volunteers, non-equity, and with strictly local reputations; a “concert performance”.

Pretty dismal sounding, huh? In fact, on this sunny Saturday afternoon, July 27, 2013, I almost didn’t go, despite my season ticket. But, ever the optimist, I argued hey, I love the play and I love Victor Herbert’s music and maybe it’ll all turn out OK. Oh, and I can relax and enjoy it since I don’t have to write a review.

Wrong and wrong. The performance wasn’t just “OK”; it was one of the most beautiful and moving musical performances I have ever seen. – – I had to write a review even if it were never read by anyone else; it was the only outlet for all of the awe and wonder in me as I left the theater.

A couple of years ago I included a brief synopsis of Rostand’s play as part of my review of the opera by Franco Alfano. Rather than repeat that review here, I refer you to an excellent Wikipedia article in case you are not already familiar with the story. Or for the complete play as translated by Thomas and Guillemard, go to the Gutenberg eBook.

We arrived at the exact moment that the librettist-lecturer Alyce Mott was beginning her pre-opera lecture and found two excellent seats with more-than-ample leg room. The lecture was well-delivered and contained some fascinating information that was new to me. In the days following the review I supplemented that information with help from Wikipedia and by email correspondence with librettist Alyce Mott and music director Bruce Herman.

I knew that Victor Herbert had written such early 20th century hits as Babes in Toyland, The Red Mill, and Naughty Marietta, but I had no idea that he had written over 50 operettas of which Cyrano de Bergerac, written in 1899, was his seventh. Nor had I fully realized the difference in the entertainment world between then and now. The 19th century was not only pre-Facebook, pre-web, pre-television, and pre-radio – it was also pre-movie house. Vaudeville was the chief form of public entertainment. Grand opera was for the elite few in the big cities – musicals and operettas were in their infancy. Families provided much of their own entertainment; the sale of piano vocals provided a large part of the income that supported a production.

Bernard Rostand’s play Cyrano de Bergerac opened in France in 1897. It was wildly successful, as was an authorized English translation, which opened in New York October 3, 1898. An unauthorized slapstick burlesque of it a opened a month later at Weber and Fields’ Music Hall and was also successful – presumably with a different type of audience. Then, the following summer, Francis Wilson, a very successful slapstick comedian who was also a skilled swordsman, decided he would make an ideal Cyrano. He became the producer of a new operetta to be based on Rostand’s play. He contracted Victor Herbert as composer, the well-known Harry B. Smith as lyricist and librettist, himself to play Cyrano, and his current paramour Lulu Glaser, a well-known actress, as Roxane.

The result was disaster. The two leads could neither sing nor act dramatically. The original tragic ending was changed to a “lived-happily-ever-after” one. Cyrano was changed from a tragic hero to a buffoon – a character Wilson could play well. But Herbert had presumably seen and been moved by the play. His music was in harmony with the original play, which meant that it was at discordant variance with Wilson’s revision – a sure recipe for a bad opera or operetta. Critics panned it utterly; New York audiences agreed with them; rural audiences on the tour were even less interested.

Cyrano de Bergerac closed after 20-some shows on Broadway, and the planned nation-wide tour was cancelled after only two cities. The operetta was lost – in both senses of the word, leaving behind only bad reviews and a few news items in newspapers or magazines.

Enter Alyce Mott, playwright, author, director of both light and heavy musical entertainment, and publisher – and a charming person. A lady mature enough to have directed an opera in Lincoln Center in 1985, who discovered the music of Victor Herbert and fell in love with him with all the fervor and zeal of a teenage groupie. Unlike a groupie, however, she is blessed with great talent, which she has used and is using to reacquaint the American public with the music of Victor Herbert. She is co-founder of The Victor Herbert Renaissance Project and Cyrano de Bergerac is but one of several Herbert operettas for which she has provided new libretti.

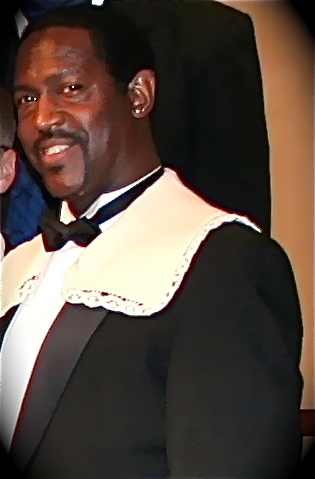

When a play, already lengthy by modern standards, is transformed into an operetta, half or more of the original dialog must be cut to make room for the music. Ms Mott used a variety of techniques to reduce a 150-page script to a 44-page libretto, including all repetitions in the musical numbers. She reduced five acts to two, and 45 characters to 14, ten of whom doubled as members of the ensemble, and only two of those had an aria. And the major role of de Guiche was assigned to a non-singing actor who, doubling as narrator, could replace an entire page of dialog by a sentence or two of description. Matthew Lee performed this role admirably, as exemplified by his opening entry, which I will quote later.

First, however, let me introduce the three singing principals, starting with the young cadet, Baron Christian de Neuvillette ably sung by tenor Orlando McCorkle who has perhaps the finest voice of the trio. As I have said before, trios (and duets) are my favorite musical forms, and Herbert gives us a couple of beauties in which McCorkle’s voice blends well with the other two.

Roxane (Mezzo Cheryl Blalock) has the first aria “I am a court coquette” in which she introduces herself:

With a glance to right, and a glance to left,

With a curtsey deep and low,

With a murmur here, and a whisper there,

and a flutter of fan, just so.

With a downcast eye, and an artful sigh,

With a smile I pay each debt.

From Cupid’s fetters free,

I’m happy as may be;

Who wouldn’t be a court coquette?

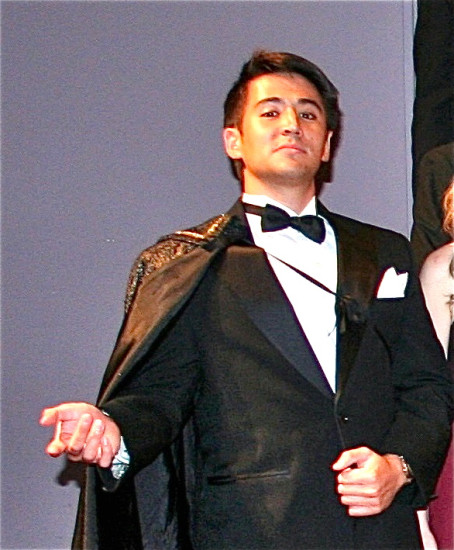

Cyrano (Robert Solis) is, of course, the main character. He describes himself thus:

Cyrano Savinien Hercule de Bergerac, at your service, my lord. As for protection, velvet, or lace – I have no need! I carry my adornments on my soul. I go about bearing only my white plume of freedom, decorated by my good name, clothed in exemplary deeds and quick wits; courage and valor swinging at my side ever ready to prick pomposity and defend those who cannot protect themselves.

and de Guiche refers to him as

the most arrogant, boisterous, brash, tempest of a man – soldier of incredible skills – rapier swift wit – audacious to the utmost.

Solis did not act the part – he lived it. His nose was his own but I could believe it was a monstrosity. He didn’t carry a sword, but he could draw and thrust and parry with only a lace handkerchief in his hand and with such realism that I could almost see the blade flashing.

Cyrano did not have any true arias, but sang several numbers with the chorus. Also, he had the lead part in the trios mentioned above and sang a couple of lovely duets with Roxane.

Ensemble (Men): Carmelo Rosada III (Minstrel), Daniel Holbert (Le Bret), Kyle Arrouzet (Corporal Louis), Rod Whitehouse (Montfleury), Larry Tom (Monk), Andrew Metzger, Paul Sherrill (Corporal Andre), Bernard Smith, Mark Blattel (Ragueneau); (Women): Beth Ann Wells, Alexandra Quinn (Lucille), Linda Solis (Cook), Carol Ann Parker (Suzette)

Finally, the part that can break or (in this case) make an operetta – the ensemble, ten of whom also took on minor roles. Their stage motion was well organized and their singing blended perfectly with the well-played orchestra.

I want to tell you, if I can, how my feelings changed from the dubious skepticism with which I walked in to the emotional elation with which I walked out. There was a break after the lecture concluded – as we resume our seats, the orchestra begins the lively overture, and I am immediately reassured that I will like the music.

As the vigorous applause dies down, a caped character rises from his seat on the aisle and strides towards the stage, declaiming as he goes:

The year, 1670. The place, Paris. I alone am still standing long after the events I am about to share with you. I’m an old man now – older and dare I admit wiser than the fellow you’ll see along the way this evening. Le Comte de Guiche at your service … Let’s slip back in time to a perfect evening in May, Paris, 1640. Louis XIII sits on the throne and lends his patronage to the wonderful Th��tre de Bourgogne where an audience is gathering for an evening of dramatic entertainment … While I have yet to make my esteemed appearance, I can share from delightful experience that … excitement begins to build as the crowd awaits the minuet which will signal the beginning of the evening’s play.

And so begins a remarkable afternoon of musical theatre. It was billed as a “concert performance”, but it was far more than that. True, the performers were “on book” and carried scripts in their hands; true, they wore mostly concert dress and costume change was confined to accessories such as head-gear, aprons, etc; true, there was no scenery and only a bare minimum of props; true, the orchestra (including the conductor) occupied the rear tw0-thirds of the stage, leaving little room for the actors. But once the operetta started the actors and singers were so thoroughly “into” their roles that I was hardly aware of any of those limitations.

Roxane sings her aria (quoted above), and my skepticism has become a cautious optimism. All doubt is removed when Cyrano and Roxane sing their first lovely duet, “I must marry a handsome man:”

Oh! Beauty’s superficial,

So they tell

Unless the proverbs err;

But ugliness is just as deep as well,

I know which I’d prefer

(Roxane) I dote upon a reputation martial

(Cyrano) And brains! Are they in your plan?

(Roxane) And brains are also in my ideal plan

(Together) But most of all,

(Roxane) {To beauty I am partial

(Cyrano) {To beauty I’m impartial

(Roxane) {I must marry a handsome man

(Cyrano) {Oh! Beware of a handsome man

Later, at their rendezvous in Ragueneau’s office, Roxane sings the lovely song “I wonder, I wonder” which leads into the poignant dialog where Roxane is asking one thing, and Cyrano is hearing something quite different

Roxane: Do I dare tell you?

Cyrano: I believe I already know.

Roxane: Ah, my childhood friend, do you still read my mind so well?

Cyrano: I would rather hear it from your lips.

Roxane: He is an amazing man!

Cyrano: You think so?

Roxane: A master of song, yet timid and shy.

Cyrano: Ah.

Roxane: He does not yet know of my love.

Cyrano: Can he know … soon?

Roxane: Oh, yes. You see he loves me, too. I saw it in his eyes.

Cyrano: A person’s soul resides in his eyes.

Roxane: So true. He is a musketeer.

Cyrano: Yes?

Roxane: In your own regiment. Noble – proud – brave!

Cyrano: Of course!

At the beginning of this dialog Cyrano believes Roxane is about to declare her love for him. Everything about Solis conveys this message: his expression, his body language, his tone of voice; he is the happiest man on earth and the feeling increases until . . . .

Roxane: And so … beautiful!

Cyrano: Beautiful?

His lips say the one word – but his body language says, “Who, me? Ah me; she must really be in love.” . . . . And then the bomb drops:

Roxane: Even his name … Baron Christian de Neuvillette. . . . I ask of you, who are so good and kind, that you might carry my felicitations to him.

Cyrano reacts as if hit by a sandbag. And Solis conveys the whole message. He doesn’t need words to finish the scene. From the apex of happiness to the nadir of despair – from denial to reality – he wordlessly is telling us “How could I be so blind; of course she can’t love a person with a nose so large. She will be happier with a young man of beauty. And I love her so much and want her to be happy:”

Cyrano: For you, Roxane, I would … I will take your message.

Is there a nobler character in all of opera? Edgardo’s love for Lucia? Germont’s love for Violetta? Cavaradossi’s love for Tosca? – None of them come close to Cyrano’s love for Roxane. It was there in the music; it was there in the words; and it was all so perfectly conveyed to the audience. There was already a lump in my throat. This is being an outstanding experience.

During the intermission I chatted briefly with Alyce Mott. She asked me how I was liking it so far. I attempted to tell her how much I was feeling, and she said, “Wait until Act II – it’s even better. Unlike many other operettas, it’s all new music – no reprises.”

She was right. The hauntingly beautiful “In bivouac reposing,” a tenor solo with cadets humming in the background, is different from any music we heard in Act I:

In bivouac reposing, warriors sleep,

In lightest of dozing or in slumber deep.

The sentinel is keeping his watch o’er all,

The rest of us sleeping ’till trumpet call.

With the cadets joining in the chorus

Around us are glowing the campfires abright,

Strange shadows they’re throwing

Like ghosts of night.

Meanwhile Cyrano has been writing (and somehow managing to deliver) daily love-letters to Roxane – letters composed in his own heart but signed “Christian”. The letters have so enflamed Roxane that she risks her life to join him at the front so that she may hear him speak them before they die together. Alas, Christian cannot deliver – he can only stumble

Roxane, the sun is in your eyes … no, no, no … that’s not right … oh dear! Roxane, there is something I must know – it’s very important. What would you say, … what if … what if I were not so handsome? What if I were … ugly? What then, Roxane?

To which she replies

No amount of disfigurement could hide your radiant soul.

and Christian continues

Roxane, I didn’t … what I mean … well, there is something you should know. …

Ironically, “a bugle’s blaring call to arms intrudes, and Christian sweeps Roxane into his arms in a lingering kiss before rushing off to find Cyrano.” – and to show his own noble nature:

She loves you, you fool! Not me! Your mind. Your words. If I spend even a few more minutes with her, she’ll know my fraud. Go to her, tell you wrote the letters. … The marriage can be annulled. I don’t want her this way! I want her to love me for what I am. Not what you are. Just now she said she would love me no matter what I looked like – even ugly.

Christian rushes off to the front; Cyrano tries to tell Roxane but irony strikes again as a clatter of artillery fire drowns him out and two Musketeers rush in bearing Christian’s dying body. I am totally immersed as they sing their exquisite trio, “Since I am not for thee:”

Roxane

The final song you sent to me,

Then perchance I’ll see,

If my unknown ideal is thee,

Yes, I will see

Christian (speaking) Cyrano sings it so much better than I

Cyrano

Since I am not for thee, sweetheart

Since I am not for thee;

Why here’s a health to him you love,

And worthy of you may he prove.

A health with three times three Sweetheart,

Since I am not for thee

Since I am not for thee, sweetheart

Since I am not for thee.

Christian (speaking) Your song

Roxane

‘Tis charming I declare,

If one who sent it I could find,

To him my heart would be inclined.

You know the song?

Christian

I know it now.

. . . . . .

{Roxane & Christian

{ Cyrano

{Since you’re the one for me.

{ Since I am not for thee.

The final scene. Cyrano, foully ambushed and mortally wounded, visits Roxane in the nunnery to which she retired when Christian died. Hiding his injuries, he asks to read Christian’s last letter (which he, Cyrano, had written) and which Roxane has worn next to her heart all these 20 years. He reads without opening the envelope:

Cyrano: “Farewell, Roxane, because to-day I die …. I know it will be today – and my heart so heavy with love I have not told. Thus, I die without telling you! No more shall my eyes drink the sight of you like wine,”

Roxane: (very quietly) Cyrano, you have not opened …

Cyrano: “Even now, I shall not leave you. In another world, I shall be still that one who loves you, loves you beyond measure, beyond…”

Roxane: Cher seigneur … it was you all along.

Cyrano: No.

Roxane: I should have known every time you uttered my name.

Cyrano: No.

Roxane: That song! Those dear letters!

Cyrano: No! No! A thousand times no …

Roxane: O noble soul! It was all you!

Cyrano: I … never … loved you.

Roxane: Even now you do. How could I have been so blind?

Cyrano: Please.

Roxane: How could you have remained so silent all these years, knowing that here in this letter lying always on my breast were your words, your tears. Not his, yours.

Cyrano: The blood was his. You pledged him your purest heart. How could I do otherwise?

Finally, the coup de gr�ce for my feelings, Cyrano’s final words, spoken over swelling under-music that continues to the finale:

Cyrano: As I lived, so shall I die! On my feet with sword in hand! … As I enter into heaven’s gates, my salute shall sweep away the stars from the very sky! Yet, I go not unadorned. One thing without stain, unspotted, from this world do I bear away, and that is … that … is … my … white plume.

(With these words, Cyrano collapses in Roxane’s arms, his great soul stilled forever)

Roxane: I never loved but one man in all my life, and now I have lost him twice.

De Guiche delivers the final epitaph:

It is possible to have all success and still feel paltry. How I envied this man! Soldier – Poet – Unfettered Spirit! Living his own life, his own way – thought, word, deed – tethered to no man but King and Country. A man the equal of Caesar or Alexander in far more ways than just the size of his most illustrious nose.

Even now, more than a week later, as I reread the libretto, I am overcome by this beautiful tragedy of humanity at its best. Would’st that instead of typing these words on an electronic computer that strips them of all personality, I were writing them with quill pen and you could see the remains of a tear upon the parchment – a tear not from the eye of Christian, � not from the eye of Cyrano, � but a tear from the eye of

P. S. You may have noticed that Cyrano’s last word was “white plume”, whereas in most other translations it is “Panache”. In a program note to the Libretto, Alyce Mott writes:

Panache From the middle French word “pennache” meaning “an ornamental plume of feathers, tassels, or the like, especially one worn on a helmet or cap.” Cyrano loves his “white plume.” It is his only decoration and his badge of courage. Because of the play’s success the English word “panache” eventually came to represent the character Cyrano’s “grand or flamboyant manner; verve; style; flair.” Please do not use this word instead of “white plume” �your audience will not know its original French meaning. The primary reason NOT to substitute this term anywhere in this libretto is that Cyrano himself would never have used such a term with regard to himself. Also this word meaning arose because of Cyrano, not before, which is why the author has chosen to exclude the word entirely.

Lyric Theatre

Gilbert & Sullivan Society of San Jose

P.O. Box 6741

San Jose CA 95150

408-986-9090

All lyrics and dialog quotes are from the original libretto (©2013 Alyce Mott)

Except as noted, photos by Kathy Tom; cropping and formatting by Philip Hodge

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on August 9, 2013.