La BohŤme is one of the most popular operas of all time.

In particular, the New York Metropolitan Opera’s production of it by Franco Zeffirelli has had more performances than any other production of any opera by the Met.¬† Indeed, the Saturday matinee on April 5 2008 was the 348th performance since it was first presented in l981.¬† Since the Live HD of that performance, there have been 4 Encore showings, culminating in the Summer Encores of July 14 and 15 2010.

I didn’t discover MetHD until April 26 2008 when I saw Daughter of the Regiment which I loved.¬† My second MetHD experience was an Encore performance of La BohŤme in May 2008.¬† It made such a strong impression on me that I immediately wrote about it just to relieve my own feelings.¬† I’m going to begin my review by giving you my first impression in full, and then adding a short section based on seeing it again this month.

| May 17, 2008

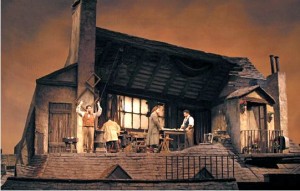

LA BOH»ME I went to the Encore showing of the New York Metropolitan Opera’s MetHD movie-theatre production of La BohŤme.¬† And I was disappointed. What is my favorite opera?¬† I can’t answer that question.¬† It depends on my mood and what operas I’ve seen recently.¬† But to the related question, “What opera affects me the most emotionally?”, the answer is La BohŤme.¬† Over the past 7 years I had seen at least five different productions – several of them more than once.¬† And every time I knew going in that when Rodolfo sang his final anguished, “Mimi”, the tears would be rolling down my cheeks.¬† But Wednesday night there was only a small lump in my throat and a mere trace of moisture in my eyes. Why?¬† Why did this production sung by international stars, accompanied by a world-class orchestra, with unbelievable sets, with skillful camera work showing close-ups of the very photogenic Mimi and the very believable Rodolfo leave me cold? The contrast with the two most recent performances I had seen could hardly have been greater.¬† Last August I attended a production by the brand new Fremont Opera.¬† A semi-staged version by a small company on a small stage.¬† As the final curtain came down I was limp. Four years ago the music students at Simpson College in Iowa showed off their talents by presenting a collection of scenes from various operas.¬† No admission – they were happy to have an audience.¬† No scenery – except for a bed and a chair the stage was bare.¬† No orchestra, only a piano.¬† They only performed the final scene so there was no build¬† up getting to know the characters through the first 3 acts.¬† In fact the preceding scene had been by a different cast from a totally different opera – I don’t even remember what.¬† And at the end I was totally wiped out. Ingredient by ingredient, they can hardly be compared: Student performers vs. international stars But, like two different non-Euclidean geometries, in one production the whole was much greater than the sum of it’s parts – and in the other, it was much less. But why this difference?¬† Why does a small college in Iowa put things together better than one of the greatest opera companies in the world? ThatĎs probably the wrong question to start with.¬† Regardless of particulars, how can any performance of this opera generate such a strong emotional reaction?¬† Part of the answer, of course, is Puccini’s beautiful music.¬† The rest, I believe is the simplicity and relevance of the story.¬† The plot is banal – almost non-existent.¬† A man and a woman meet and experience love and loss.¬† What could be simpler?¬† I could be that man; you could be that woman.¬† What could be more relevant? Puccini’s genius is that he can find exactly the right music to tell this simple story.¬† I’m not much of a musician.¬† If part of the music were inappropriate, I might be able to pinpoint that fact, but I would no idea how to fix it.¬† But here there is nothing to fix.¬† Every note, every harmony, every volume, every interval is perfect. O. K., the opera is perfect.¬† Then why did Wednesday’s performance leave me dry-eyed while the tears flowed freely at the student performance and the semi-staged performance (and at Pocket Opera and West Bay Opera performances in 2002)?¬† Let me review the action as I remember it, from when Mimi is carried into the garret room of the four bohemians.¬† Everyone¬† except Rodolfo and Mimi knows that she will die within the hour.¬† Tension starts to build as they each try to do something for Mimi: sell their jewelry, call a doctor, pawn an overcoat, etc.¬† The others go off on their errands, leaving the lovers to sing their beautiful duet about how she will soon get better.¬† The others return with their gifts.¬† Mimi, on the bed at one side of the stage appears to drift into quiet sleep; Rodolfo wanders to the opposite side of the stage; the others are somewhere in between. Mimi’s arm drops limply from the edge of the bed.¬† We, the audience are the first to know that she has drawn her last breath.¬† Tension builds as the others notice that she is dead.¬† Knowledge of this fact appears to move inexorably, almost palpably, across the room.¬† Only Rodolfo, turned away from the others, is ignorant.¬† He senses a change in the atmosphere.¬† He turns and looks at them one by one as the knowledge seeps into his consciousness.¬† He looks at Mimi, cries her name, and hurls himself at her.¬† Final chords.¬† Final curtain.¬† [Even as I sit alone in my office and write these words, I have to take off my glasses and reach for the Kleenex]. Now it’s easy to see where the Met went wrong.¬† They were a victim of their own technical abilities.¬† They were so busy showing close-ups of each person as he or she first became aware of Mimi’s death, that we missed the overall effect.¬† The power of the scene is the build up of tension as we wait for Rodolfo to find out and to react.¬† He is the focus of the scene.¬† He is the one who has lost his lover; the others have merely lost a lovely friend.¬† To be sure, when I am watching a stage performance, part of me is noticing which person is just now discovering Mimi’s death.¬† But Rodolfo is the one I identify with.¬† I am watching the whole stage as the news moves across the room, waiting for the release of his final cry and action.¬† I’m not interested in a close up of how Musetta or Colline express their grief. But at the Shoreline Cinema the camera person wouldn’t let me do that.¬† For a few moments there, Rodolfo was forgotten.¬† .¬† .¬† .¬† And I felt cheated out of my tears. But for 3¬Ĺ¬† acts it was a wonderful performance. Philip Hodge |

OK.¬† I’m back in the present, July 2010.

I had reread my earlier review before heading for the Cin…Arts theater in Palo Alto, so as I entered it Thursday afternoon, my thoughts were different than they usually are when I go to an opera.¬† I knew I was going to see again exactly the same performance I had seen and written about before, so my thoughts were partly analytical: how would my reactions compare with what they had been two years before?¬† Answer: they were basically the same, only more so – there was too much jumping around of camera views.

I particularly noticed it in Act III.¬† In a live theater it is a quiet peaceful scene with gently falling snow. The introductory business with the laborers at the gate, Mimi’s plea to¬† Marcello , her beautiful duet with Rodolfo when they decide they will wait until spring to part . . . they all seem to take place in slow motion against a background that gives perspective to human emotion compared with a serene nature.¬† But the camera keeps jumping around and destroying that perspective.¬† I was so conscious of that switching that I started counting the seconds that we kept the same view.¬† It was as if the camera people had been told, “Remember, the American public all have limited attention spans.¬† Ten seconds is the absolute maximum without changing the camera – five is better.”

I love close-ups.¬† Seeing the expression on singers’ faces adds a great deal to my enjoyment of opera.¬† But this was too much and often too close up.¬† For Puccini in particular, listen to the music and move the camera accordingly.

The final scene of Act IV began well.¬† Musetta brings Mimi in, the lovers are reunited, the others go off on their errands of mercy, Mimi and Rodolfo sing their beautiful duet.¬† I surrender myself to the scene; the tears begin to form.¬† At that point I should have shut my eyes and just listened to the music – but I didn’t and the mood dissipated.

Oh well.¬† You win some (the marvelous La Traviata I saw last week, for example) and you lose some.¬† But if the Met Encores this performance again, I’ll stay home, thank you.

The Opera Nut

CineArts

3000 El Camino Real # 6

Palo Alto, CA 94306-2110

(650) 493-3456

www.cinemark.com/

Photos (except as noted) by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on July 23, 2010.