I was raised on Gilbert & Sullivan.

Scores, libretti, and 78-rpm records were around the house when I was growing up. By the time I was in high school I could sing all of the words from many of the songs in almost all of the operettas, regardless of original voice range – I’d just sing in my own key. For example I knew the Mikado’s bass aria, Make the punishment fit the crime, and Yum-Yum’s beautiful aria, The sun, whose rays are all ablaze from the beginning of Act II.

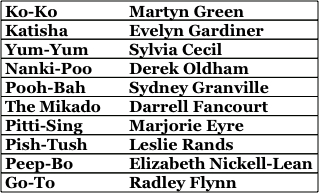

The D’Oyly-Carte Opera Company came to New York in 1936 when I was in high school, and we took the train into the city every Friday to see ten of the G&S operettas. For the following week the house would be full of songs from last Friday’s opera. The names may not mean much today, but back then Martyn Green (Ko-Ko), Derek Oldham (Nanki-Poo), Sidney Granville (Pooh-Bah), Darrell Fancourt (The Mikado), and Evelyn Gardiner (Katisha) were legendary for singing major roles in all of the G & S repertory. Fancourt, for example, was a leading member of The D’Oyly-Carte company for 33 years until his death in 1953. During that span he sang in over 10,000 performances including over 3,000 as the Mikado.

Martyn Green (1889-1975) was the principal comedian from 1934 to 1951 except for three years during World War II. He regularly played the lead comic in all 9 of the major G & S operettas. His performance schedule was unbelievable: 8 performances a week! A typical week during the run in New York had him singing Major-General Stanley from The Pirates of Penzance on Monday evening, Tuesday evening, and Wednesday both matinee and evening, followed by Ko-Ko from The Mikado on Thursday, Friday, and twice Saturday. He’d have Sunday off and then the same schedule next week with The Lord Chancellor (Iolanthe) and Robin Oakapple/Sir Ruthven (Ruddigore). And so on through all nine roles.

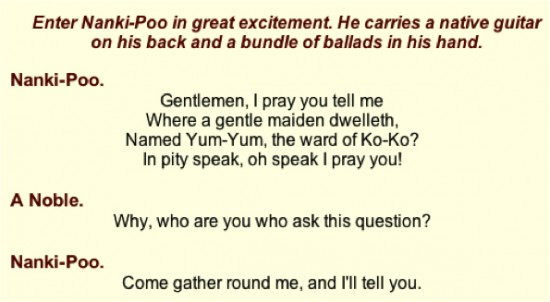

Fast forward a couple of years and I was at Antioch College in Ohio where I was in the chorus for three G & S operettas: Yeomen of the Guard, The Mikado, and The Gondoliers. I was A Noble, and had the one solo line of my entire career:

I made a point of noting which Noble sang that line; in the lobby after the performance on Sunday I made a beeline for Robert Dorsett. When I told him I was glad to see that important role sung so well 70 years after I had sung it, he agreed to pose for the above picture.

I still have a vivid memory from one of the rehearsals at Antioch. Our director was the Dean of students. He seemed incredibly ancient to us undergraduates although in actuality he was probably about 50. Nanki-Poo and Yum-Yum were sung by a couple of undergraduates, Don and Bee Jay. Don had a sweet tenor voice but was inordinately shy and stiff as an actor; Bee Jay was a good-looking young lady with a nice soprano. Any of us young males in the chorus would have welcomed a chance to give her an amorous kiss as called for at the end of their cute duet in Act I, This is what I’ll never do, but the Dean thought Don was not doing a very good job of it (we all agreed). After a couple of unsuccessful attempts to talk Don into a better performance, the Dean lost patience: “This is how it should be done.” He grabbed Bee Jay, planted his lips on hers, bent her over, and held the pose for several beats. Now-a-days I suppose this might result in a lawsuit (“DEAN ACCUSED OF ASSAULTING CO-ED ON STAGE”), but we all thought it was hilarious. Although this was long before email, facebook, texting, and twitter, the news was all over campus within 24 hours.

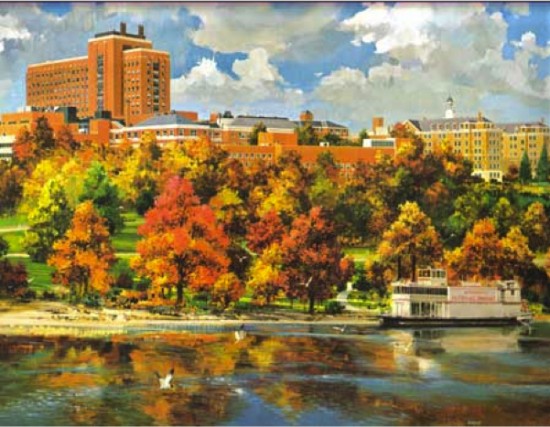

Fast-forward many decades during which I’d seen G & S performances in theatres all over this country. During the 70’s and 80’s I was professor of engineering at the University of Minnesota. I was, of course, a subscriber to the annual performances of the amateur Gilbert and Sullivan Very Light Opera Company and saw the Mikado sometime during the 90’s. However, the specific memory I have of those Minnesota years is not a stage performance but an incident that shows how deeply G&S was engrained in my personality. I was walking across campus at my usual extremely fast pace when I passed a group of three young women of obvious Asian ancestry. The apparently found something amusing in my appearance and were obviously giggling as I strode past them. I instinctively started humming, Three Little Maids from School and burst into full-voiced rendition of all the words as soon as I was safely out of their earshot.

A couple of decades later, imagine my feelings on Wednesday, August 21, 2002 when my wife and I walked into the Savoy Theatre on the Strand in London’s Soho district to see the D’Oyly-Carte Opera Company perform The Mikado. The original theatre was gutted by fire in 1990 but was restored according to the original blueprints with a fancier entrance and an added story. The actual performance was interesting even if not the best I’ve ever seen. But oh, the aura of the place and the flood of memories it brought back. Memories . . . . Memories . . . . Memor –

Molly Mahoney as Pitti-Sing, Lindsay Thompson Routh as Yum-Yum, Robert Vann as Nanki-Poo and John Melis as Pish-Tush; Photo by Lucas Buxman

Hey, wake up! There are still a few things to say about Act II of the wonderful Lamplighters production. First, Ko-Ko brings the bad news that according to law, if a married man is executed, his wife is buried alive. Yum-Yum demurs at this, “it’s such a stuffy death!” The wedding is off. Nanki-Poo says “I can’t live without Yum-Yum. This afternoon I perform the Happy Dispatch.” Ko-Ko reminds him:

Ko-Ko. As a man of honour and a gentleman, you are bound to die ignominiously by the hands of the Public Executioner.

Nanki-Poo. Very well, then � behead me.

Ko-Ko. What, now?

Nanki-Poo. (putting his head on the block) Certainly; at once.

Pooh-Bah. Chop it off! Chop it off!

For a moment we see the touching reality beneath the farce as Ko-Ko takes a realistic look at himself and realizes, “I can’t kill you � I can’t kill anything! I can’t kill anybody! (weeps)”

Suddenly he returns to the farce with an inspiration: “Why should I kill you when making an affidavit that you’ve been executed will do just as well?” The Mikado is heard approaching, so Ko-Ko swiftly shoos everyone off stage, silencing Nanki-Poo’s objections with, “Take Yum-Yum and marry Yum-Yum, only go away and never come back again“.

The Mikado (Wm H Neil) makes his triumphal entrance to the Japanese air, “March of the Mikado’s troops.” (also used by Puccini in Madama Butterfly), but is constantly interrupted and upstaged by “his daughter-in-law-elect” (Katisha, played by Sonia Gariaeff) with some delightful mugging on both their parts. He then goes on (without interruption) to his famous A more humane Mikado aria from which I quote only the last verse and chorus:

The billiard shark who any one catches,

His doom’s extremely hard �

He’s made to dwell �

In a dungeon cell

On a spot that’s always barred.

And there he plays extravagant matches

In fitless finger-stalls

On a cloth untrue

With a twisted cue

And elliptical billiard balls!

My object all sublime

I shall achieve in time �

To let the punishment fit the crime �

The punishment fit the crime;

And make each prisoner pent

Unwillingly represent

A source of innocent merriment!

Of innocent merriment!

It was not indicated in the original libretto, but in the early 1920’s Darrell Fancourt paused for a beat before the chorus to produce a memorable evil laugh – and ever since bassos singing the part have tried to produce their own signature laugh. Neil’s laugh is right up there with the best of them. It takes a beat to start. His grim visage begins to crack and a rumbling chuckle from deep in his belly begins to emerge. The chuckle grows to a laugh and progresses to a wheezing roar that seems to come from his entire body. The court, of course, imitates him, a beat or so behind. Suddenly the Mikado has laughed long enough. He stops on a dime and glares at the court who immediately stop in mid-wheeze.

The third and final verse of Ko-Ko’s wonderful I’ve got a little list contains the lines,

And apologetic statesmen of a compromising kind,

Such as � What d’ye call him � Thing’em-bob, and likewise � Never-mind,

And ‘St� ‘st� ‘st� and What’s-his-name, and also You-know-who �

The task of filling up the blanks I’d rather leave to you.

However, George Grossmith, who played Ko-Ko on opening night, was not only a great singer and actor but also an accomplished mime. Although no names were mentioned, it was obvious to the London audience that the list included such prominent statesmen as Gladstone and Lord Salisbury. When other players took the role of Ko-Ko in later generations and/or other locales, they would change the mummery to indicate notables recognizable to their audiences.

At some point Ko-Ko began to change not only gestures but some of the words. Early libretti refer to That singular anomaly, the lady novelist, but in United States that line had been replaced by That singular anomaly, the prohibitionist. I remember our 1939 Antioch College production as introducing local references in an additional verse presented as an encore – I believe this was common practice, at least among amateur productions.

Lamplighters went even further. They kept only the first verse of Gilbert’s original and wrote two new verses with lines that were totally appropriate to California today and to the Gilbertian spirit:

There’s the senators and congressmen who send our boys to war

Perhaps they should enlist

I don’t think they’ll be missed

And the CEOs who cook the books behind the boardroom doors

They all should be dismissed

I’ve got ’em on the list

Since so much of this review has been personal, let me close with a personal plea to F. Lawrence Ewing:

If you’re looking for professors who are sometimes not profound

Spare this humble essayist

By my readers I’d be missed

To hear you sing King Gama next I want to be around

To see you shake your fist

(Gama’s a misogynist)

. . . . .

All quotes are from Web Opera.

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on September 24, 2012.