How do you start with an 800-page book that has stood the test of time and create a three-hour opera from it? Here are a couple of quotes from Composer Jake Heggie’s fascinating article in the program:

When I read [the book] I realized how essentially musical and operatic it is. . . . The drama could certainly fill an opera house, and it struck me that the music was already there. I could hear musical textures, rhythms, orchestral and vocal colors as I considered it. . . . .

I wrote a chant for Queegqueg and about 60 additional pages of music. . . . in agony I discarded everything I had written. It was good, just not good enough. What was blocking me? I realized that all of the characters had become real to me – except for Ahab. And without Ahab, you don’t have Moby-Dick. . . . Halfway through the first act libretto was the great monologue “I leave a white and turbid wake.” And there was the aching human being – the fully formed individual. The music for Ahab emerged and the world of the opera cracked open for me.

After completing that aria, I was able to go back to the first measure and compose straight through Act One.

I am not an artist, in any sense of the word. I read Heggie’s words; I believe I understand what he is saying; I am utterly unable to imagine what is in his mind when he writes: “the music was already there.”

Whatever it is, it works! The entire opera takes place on Ahab’s ship, the Pequod or in the water surrounding it. The essence of the story including presentation and development of the principal characters in the novel are elicited in 5 separate days culled from the 16-month voyage of the Pequod.

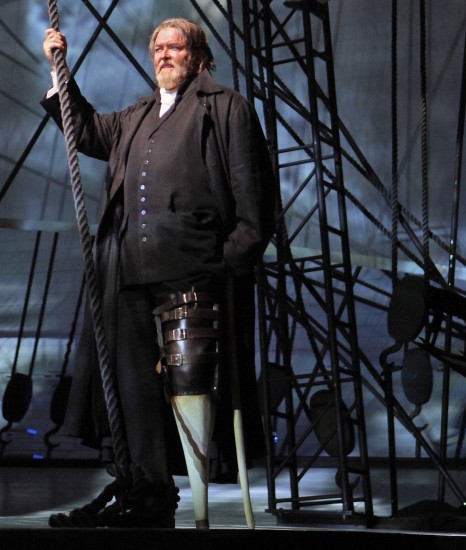

It works! And a large part of why it works is tenor Jay Hunter Morris. He was not acting the part of Ahab, he WAS Ahab – monomania, absolute authority and all. Take a close look at those two photos of him. The skilled make-up is part of it, of course. But no make-up person can turn Morris’ natural laughing eyes and friendly smile into Ahab’s icy glare and uncompromising mouth. It takes a real actor to do that kind of transformation – and more. From my seat in row T, I could only imagine the facial detail that I now find in the photos.

The three harpooners, Jonathan Lemalu (Queequeg), Bradley Kynard (Daggoo), and Carmichael Blankenship (Tashtego) cross their harpoons as Jay Hunter Morris (Captain Ahab) brandishes his gold doubloon

But I didn’t need to see it to know that the arrogance and monomania was there. It was in his stance – his every gesture – every step he took. Above all it was in his rich commanding voice. From his first note to his last you knew that here was a person who would brook no opposition.

All of this, mind you, while sporting a peg leg. One could no more play Ahab without a peg leg than one could play Marie Antoinette without jewels or Abraham Lincoln without a beard. You can tell from Jay Hunter Morris’ studio picture that he is far too intelligent to take seriously the idea of cutting off his real leg in the interest of artistic verisimilitude, so the costume people are presented with a real challenge. The peg is a single piece of unpainted beech wood with an ingenious harness which straps it to his upper thigh as Morris kneels on it. Thus every moment that he is on stage half his weight is supported by his left knee with the lower half of the leg sticking out behind. But the rest of his costume is designed so that I never could spot the real left foot either live in the theater nor in any of the photos.

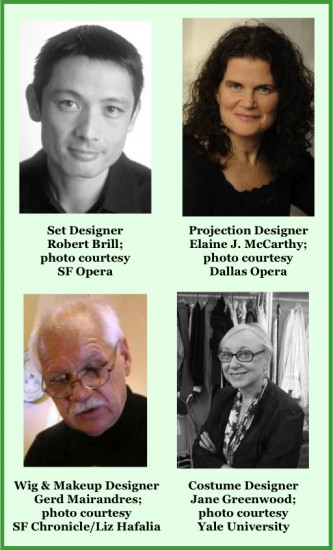

A new dimension is being added to the world of opera – Projection Design. Just last week in my review of Tales of Hoffman, I commented on the fantastic video scenery produced by West Bay Opera – a small high quality opera company right here in Palo Alto. Well, as befits their international reputation and orders-of-magnitude larger budget, San Francisco Opera’s Designers produce effects that are even more astounding.

The back of the stage is completely filled with a TV screen with moving scenery appropriate to the view from whatever the stage is currently representing. Much of the action takes place on the Pequod‘s deck. Here we see the lower part of the mast and an incredible mass of rigging and rope ladders. The lower part of a couple of sails is represented by scrims with gently curved bottom edges that can be raised or lowered. The actual sails, of course, would be made of heavy opaque canvas, but the use of translucent scrims leads to much more dramatic visual effects. The back screen shows a calm ocean under clear skies. A pod of whales is sighted, and Ahab reluctantly agrees to lower the whaling boats.

The back screen now changes to show only ocean as it might be viewed from the Goodyear blimp. Several of the seamen climb up well camouflaged steps at the rear and appear to be just sitting in the ocean as if supported by invisible noodles. Suddenly a great flurry of curved white lines of lights streak across the screen, antic a bit and then form themselves into three whaling boats, each surrounding a column of the sitting men, as shown in the above photo. The seas get rougher and one of the boats capsizes as shown by convincing manipulation of those curved lines of light. The sailors appear to be struggling in the water, but they are soon rescued except for the cabin boy Pip (Talise Trevigne) who is lost in the dark ocean.

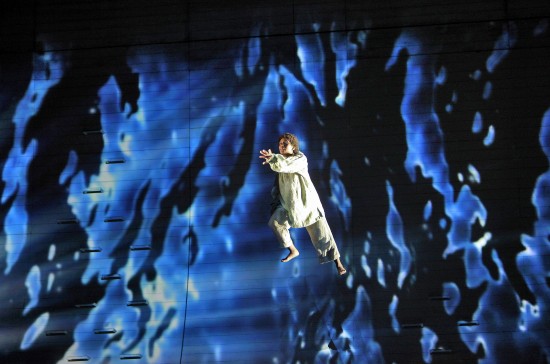

The scene changes to show the part of the ocean where Pip is valiantly “swimming” – and singing, of course. Actually Trevigne is supported by a cable and shoulder harness, but they are virtually invisible against the darkly heaving ocean – the scene is tense and realistic – one boy lost and alone in the night sea.

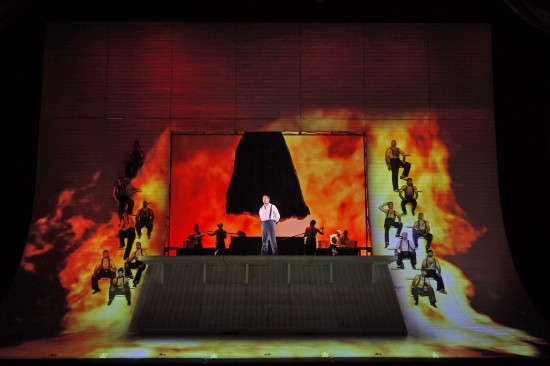

Tension mounts as we leave the struggling Pip to go back on deck where a whale is being butchered for its oil. An eerie red light symbolizes the omnipresent whale blood that would be spattered over everything. It continues to grow as the mate Starbuck (Morgan Smith) notes a serious oil leak in the ship and demands that the ship head to the nearest port for repairs. Ahab refuses and comes close to executing Starbuck – but instead just demands he go on deck.

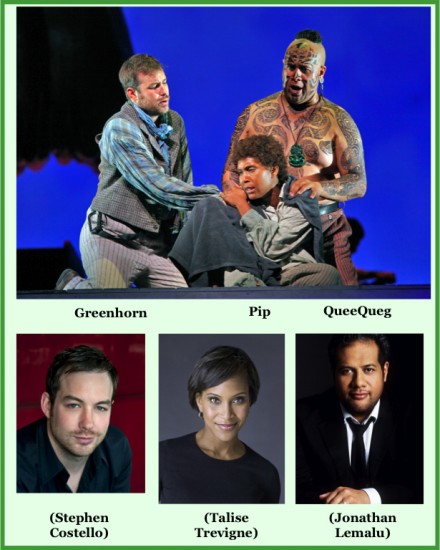

Pip has been found. The cabin boy is brought aboard more dead than alive but is nursed with loving care by Greenhorn (Stephen Costello) and Queequeg (Jonathan Lemalu). Note a couple more examples of the skill of the make-up and costume designers. Queequeg’s body tattoos are temporary water-based silicone tattoo transfers that are closely modeled on traditional Maori tattoos. The application process takes about two hours, but lasts for two performances. Since performances are half a week apart, that implies that Jonathan Lemalu spends half his days wearing them in civilian life!

Also note that Pip, the cabin boy, is a trouser role. Indeed Talise Trevigne’s powerful soprano is the only female voice we hear during the entire opera.

Starbuck finds Ahab asleep in his cabin. He sings about how the ship is doomed and he with it. He will never again see his wife and son. He picks up Ahab’s loaded gun, contemplates using it, but eventually puts it down and leaves the cabin as the curtain descends.

Another year has passed. Moby Dick has not been sighted and the crew has settled into a comfortable routine. They sing a cheerful work song. Greenhorn and Queequeg have become best friends. Suddenly Queequeg collapses, says he is dying, and asks Greenhorn to see that a coffin is built in which he will float to the end of the ocean where earth meets heaven.

Meanwhile a storm has been coming and now arrives. Lots of dramatic action, lightning, and music, including St. Elmo’s Fire playing in the rigging. The scene ends in tension amid cries of “The mast! The mast!”

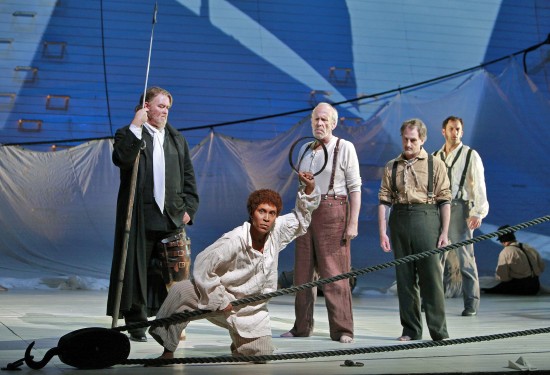

Act II, Scene 2: Jay Hunter Morris (Captain Ahab), Talise Trevigne (Pip), Robert Orth (Stubb), Matthew O’Neill (Flask) and Morgan Smith (Starbuck)

The next morning the storm has passed and the Pequod has survived. Another ship, the Rachel, looms up beside them, evidenced by large dark-blue sails appearing on the back screen. The voice of Captain Gardiner (Joo Won Kang) is heard asking for Ahab’s help in finding his lost son. Ahab refuses, still intent on his mad pursuit of Moby Dick, and the two ships part.

As they sail away Ahab and Starbuck have a deep conversation about the families they have left behind. Ahab really listens to the mate for the first time and sees another human being with a life and soul of his own. His madness seems to leave him and he is about to agree to Starbuck’s plea and head for home when suddenly he spots a whale in the distance. It is huge. It is heading towards the Pequod. IT IS WHITE – and Ahab’s mania returns in spades.

Boats are immediately lowered and manned. Ahab himself takes the place of Queequeg as harpoonist of the central boat. Moby Dick approaches and sinks the other two boats with dramatic video effects as the white lines break into smaller pieces and twist at random angles to each other. The whale readies his final charge. All the men in Ahab’s boat dive over to side in a vain attempt to escape. Moby Dick drives straight toward the Pequod – towards the audience. As he rushes past Ahab we can see his giant eye almost fill the screen. The captain drives his harpoon into him as ship and boat both break into pieces and sink – and Ahab sinks slowly beneath the water, defiant to the end.

Act II, Scene 3: It is many days later. The sky is clear, the sea is calm. The only object in sight is Queequeg’s coffin floating in the ocean with Greenhorn lying on it, barely alive. The Rachel looms up in the distance, approaches, and lets down a cable to haul Greenhorn aboard. He steps onto the giant hook and is pulled up as Captain Gardiner asks who he is. As he disappears at the top of the stage he responds, “Call me Ishmael!” These last three words of the opera are, of course, a pre-echo of the famous first three words of the epic novel, the implication being that Greenhorn-Ishmael-Melville is now headed back to Nantucket to record the tale for future generations to contemplate – and for Heggie-Scheer to complete the circle and compose the opera which relates the events which end with “Call me Ishmael”, ad infinitum.

POST SCRIPT 11/3/12

I enjoyed my first viewing so much that I saw Moby Dick again last night. As is usually the case, I enjoyed it even more the second time. Rereading what I wrote above, I realize that I never said explicitly how perfectly the music fit the action. It did. This time I concentrated more on noticing how the music, the action, the words, the costumes, and the astounding special effects all fit together to make a glorious whole. Conductor Patrick Summers deserves much of the credit for keeping the orchestra so in balance with the soloists and chorus.

I also paid more attention to the music per se and was pleasantly surprised to find that I quite enjoyed it. It was fascinating to hear a progression of discords making a certain amount of sense in themselves and suddenly resolving into an old-fashioned major chord – but not to stay there long enough for me to get complacent about it. There was an occasional song with a decidedly hymn-like quality and one with a rousing 19th century dance beat.

Last night’s performance was the last of eight which gave it an extra fillip throughout and made the curtain calls special. It seemed as if the whole cast had achieved a feeling of unity over these eight appearances and I could sense a delicious ambiguity of emotions: elation for a “mission accomplished” and sadness over the ending of a wonderful adventure.

The audience was part of it too. The applause was loud and the audience gradually rose to its feet until Jay Hunter Morris strode on stage with two good legs and virtually all of us were standing. I didn’t see how we could get any louder, but when composer Jake Heggie came out and took a bow we did!

Moby Dick premiered in Dallas in 2005 and was seen in Calgary, San Diego, and Australia before coming here. Keep your eyes open for where it goes next, you jet-setters, and join the lucky denizens of that metropolis in seeing the modern classic again. AND San Francisco Opera is collaborating with WNET to produce an HD version of this production which will appear on PBS sometime next year. A plethora of good news.

Remaining performances are:

Tuesday, October 23 2012, 8:00 Friday, October 26 2012, 8:00

Tuesday, October 30 2012, 7:30 Friday, November 2 2012, 8:00

To buy tickets go to San Francisco Fall 2012

San Francisco Opera

301 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94102

(415) 861-4008

sfopera.com

Except as noted, all photos by Cory Weaver, San Francisco Opera

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on October 23, 2012.