The magic begins with the outer curtain. When we take our seats on the side aisle in row S, we see an enormous black triangle in a field of scrolled gilt.

The lights dim. A solitary figure walks on stage in front of the curtain and is spotlighted. He is David Gockley, General Director of San Francisco Opera, wearing a business suit and a San Francisco Giants baseball cap who welcomes “the three thousand loyal opera fans here at War Memorial Theater and the more than ten times that number at AT&T baseball park” – a reminder that we are watching a special performance of AIDA which is being simulcast live and shown for free on the giant screen at the baseball park.

He gives his little welcoming speech interrupted by frequent applause, and exits, immediately followed by more applause as Maestro Nicola Luisotti strides to the podium. The overture begins, quiet and contemplative, indicating that we are about to hear a story. As it continues through its wide range of volume, tempo, moods, and snatches of familiar melodies, lights go on behind the front curtain and we realize that it was only a scrim. It soon rises to reveal the front of the king’s palace.

Amneris (Dolora Zajick), Radames (Marcello Giordani) and King of Egypt (Christian Van Horn) showing vertical columns and triangular opening

Near the back of the stage is a wholly black center draw curtain of unusual cut. The leading edge of each half is not vertical but is inclined about 60 degrees so that in order to fully close the curtain at the bottom the tops must have a large overlap. At present both halves have been drawn back a few feet thus creating an open triangle, which serves as a stage entrance. By independently but smoothly manipulating the two halves of the curtain this triangular opening can be made to grow, shrink, or move sideways.

Radames, sung by international star Marcello Giordani walks on stage, the music blends smoothly from the overture to Act I, and Radames starts his hauntingly beautiful Celeste Aida aria. I had heard Marcello Giordani this summer as Calaf in the MetHD Turandot, and with his opening notes I knew that I was in for a very special evening’s entertainment.

Next on stage was Amneris, sung by Dolora Zajick who first sang the role with SF Opera in 1989. I had heard her on HD or television as Eboli in Don Carlo and as Azucena in Il Trovatore, but this was the first time I had seen her live. Her performance was outstanding. I was particularly impressed by her range of emotion in Act II where she is all sweetness as she tells Aida to confide in her not as a slave but as a friend, but turns instantly into invective and hate when she learns that Aida loves Radames.

This was the first time I had seen or heard Michaela Carosi, our Aida. I sort of take it for granted that any Soprano who can get herself cast in the lead for a major opera company will make those fortissimo high notes sound like music rather than screeching. What particularly impressed me about her singing was the way she floated her anguished prayer, the final pianissimo soft and clear and audible at the end of Scene 1. The audience didn’t dare breathe until the last harmonic had died away.

Aida’s father Amonasro who is also King of Ethiopia does not appear until the prisoners are brought in as part of the triumphal march in Act II. Marco Vratogna plays the role more savagely than I recall other baritones doing. Let me put it this way: it is easy believe that in his SF Opera debut last year, he sang the role of Iago.

There is no scene in all of grand opera that invites excess more than the Triumphal March at the end of Act II. Performances at the old Met in New York were notorious for the presence of live elephants on stage; in their recent HD simulcast they settled for live horses. Smaller companies settle for humans pulling carts loaded with treasures. They triple the apparent number of supernumeraries by having one group march across stage from left to right, race madly back offstage to the left as soon as they are out of sight, possibly changing a wig or a jacket as they go, and march across again in a new persona.

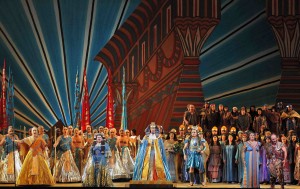

There wasn’t a lot of marching here, but they certainly managed to get a lot of people on stage – 140 to be exact, including 9 dancers and 5 acrobats. Musically, there were 7 principals, 6 trumpeters, and 80 chorus members on stage, 66 instruments in the pit, and a dozen more brass behind the stage. With everyone in full costume and full voice it was quite a spectacle for eye and ear. My one complaint with the staging (in fact, my only complaint about anything in this superlative performance) was that the king’s throne was placed at the very front of the stage, back to the audience. The result was that the King (Christian Van Horn) got a fine view of everything, but a substantial part of the dancing and acrobatics was blocked from my view.

The dancing and acrobatics took the place of the traditional display of the spoils of war. But not of the elephant factor. There was only one elephant, but what an elephant! A half dozen or so men supported his trunk on poles and did a marvelous job of weaving it about most realistically. Each ear was more than 12 feet in height and was supported by a similar crew. Each tusk had its own smaller crew, and I’ve no idea how many men supported the howdah atop it with Radames standing proud and triumphant. As I recall, the tail didn’t even make it on stage.

I can’t say enough about the sets and staging. I don’t know who is responsible for what, but I wish that Director Jo Davies, Production Designer Zandra Rhodes and Lighting Designer Christopher Maravich had all taken individual bows during the curtain calls.

In the opening scene there were numerous colorful columns, which successfully broke up the vast space of the stage and preserved the intimacy of the encounters between the three principals. There were three or four of the bias-cut back curtains used in different scenes with different size triangles.

Egyptian symbols were present in abundance and in a variety of sizes: the evil eye, the rays of the sun, and triangles reminding one of silhouettes of the pyramids. In the trial scene in Act III Amneris is alone on the forestage. Immediately behind her is a “wall” of part of the outer edge of the sunrays as long panels with two-foot gaps. The trial is talking place behind this wall. We hear everything but only see a few shadowy shapes. Amneris keeps moving back and forth peering through one gap or another to see what’s going on.

I can’t imagine a better staging of the final tomb stage. It begins with an empty stage with the biased curtain drawn in only the least little bit. A cage is lowered from above, Radames steps out, the cage is withdrawn. He is alone in the vast tomb. But no. Aida is there too, to die in his arms. As they sing their beautiful final love duet, the curtain slowly closes. Realistically, of course, this all takes place in total darkness, but with necessary poetic license the two lovers are spotlighted.

The music here is a perfect blend of the orchestra, the offstage priests chanting their hymns, and the love duet. Amneris comes quietly on the dark stage from the side with only a faint spot and adds her prayer for forgiveness for her rancor and redemption for their souls. The curtain closes slowly but inexorably, narrowing and shortening the visible part of the tomb. When the space is no longer big enough for the lovers to stand they fall to their knees, sink lower, are lying entwined on the floor. As they sing their last notes, the triangle shrinks to a pinpoint then to zero. The orchestra plays its last pianissimo chord. After the briefest appreciative pause, the audience bursts into clamorous applause.

The opera is over. But not the evening’s entertainment! Before I describe the highly unusual curtain calls, I have to get a pet peeve off my chest.

Long ago my parents taught me that the applause after a theatrical performance was an integral part of the performance. Both the audience and the performers needed it as a bridge between the imaginative world of the theater and the real world we are returning to. Furthermore, it was only polite to give the actors a token of our appreciation for what they had been giving us for the past couple of hours. It saddens me to report that fully ten percent of the opera audience in San Francisco are exceedingly rude. Before the last echoes of the final chord have died away they are on their feet rushing up the still dark aisle in their quest to beat out the rest of us in getting to the taxi line, the parking garage lineup, or whatever. A pox on them.

Hao Jiang Tian (Ramfis), Dolora Zajick (Amneris), Christian Van Horn (The King of Egypt), Marcello Giordani (Radames), Micaela Carosi (Aida) and Marco Vratogna (Amonasro) with the San Francisco Opera Chorus

Enough venting. The front curtain went up to reveal a row of the very minor characters. They bowed to applause, then the curtain behind them went up and we saw another row. Again, a bow, another curtain raised in the rear, and we saw the whole magnificent chorus. By now all of the rudies had left so it was clear that when we stood up it was to start the standing ovation that continued and continued.

Then the fun started. Conscious of the fact that the proceedings were still being simulcast live to AT&T Park, the two solo dancers ( David Mahoney and Chiharu Shibata) came on stage, still wearing their costumes but with Giants baseball caps on their heads. The applause was now accompanied by laughter, which continued as the soloists came on one by one to bow and continue the fun and add to it. I don’t recall who wore what, but Giants jackets appeared over the costumes and several soloists carried Giant orange #1 Styrofoam fists. The volume seemed to go up a notch for each of David Lomeli (Messenger), Leah Crocetto (Priestess), Christian Van Horn (King of Egypt), Hao Jiang Tian (High Priest Ramfis), and Marco Vratogna (Amonastro). Shouts of “Bravo” and “Brava” were added for Marcello Giordano and Dolora Zajick, and reached a frenzied climax for Micaela Cavarosi. When she went to the wings to get Maestro Nicola Luisotti, he came center stage, faced the audience in batting stance, and swung his baton to send an imaginary home-run ball towering over the top balcony.

Corny? Could be. But a reminder that Grand Opera is not just for the moneyed elite who can afford seats in Memorial Hall (and for the lucky press corps with their comps), but also for the thirty thousand who were seeing it for free at the ball park.

And as a bridge back to reality from the emotional tension of the final scene to a two-block walk through the balmy night to our motel for a good night’s sleep.

Ciao – –

The Opera Nut

AIDA by Giuseppe Verdi

Co-production with English National Opera and Houston Grand Opera

Libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni

Approximate running time: 3 hours with one intermission

Sung in Italian with English supertitles

PRODUCTION NEW TO SAN FRANCISCO

September 29�-� (7:30 p.m.);

October 2�-� (8 p.m.),

October 6�-� (7:30 p.m.), 2010

___ �-� OperaVision performance

(Also 5 performances in November and December with a totally different cast)

San Francisco Opera

301 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94102

(415) 861-4008

sfopera.org

Photos by Cory Weaver, San Francisco Opera

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on September 27, 2010.