Last Sunday, April 22, 2012, I saw my fourth production (and my sixth performance) of Faust in the last two years – and next Sunday I plan to go again and see Opera San Jose’s other cast.

(Search for my other reviews of Faust on Splash or on my blog.) It may not be my favorite opera, but it’s high on the list of operas that I don’t get tired of. First, of course, is the music. All of it is eminently listenable, and I don’t think I could ever get tired of The Jewel Song, The Waltz, or The Soldier’s Chorus – to say nothing of the ethereal notes that end the opera.

But there is another reason. Every production of Faust is different. Offhand, I can’t think of any other opera in which the composer allows the director so much freedom of choice. I use the word “allows” in two senses. The obvious meaning is that neither the libretto nor the comments on the score specify certain details. But more important, as I’ve said before, the direction, the libretto, and the music must all tell the same story. If the music is unmistakably dire and foreboding, then the director cannot make the action light or optimistic. (The mere fact that he “cannot” do something does not guarantee that a director “will not” do something – it means that if he does, the result is, in my opinion, a bad production.)

Take the opening scene, for example. Faust is a very learned old man. He has spent his entire life trying to find the meaning of the universe. He realizes that he has achieved nothing and decides to take his own life. He hears some young people and stops to muse I have wasted my life attempting the impossible. I’d sell my soul to the Devil to live it over again. I’d devote myself to pleasure instead of this vain quest for knowledge.

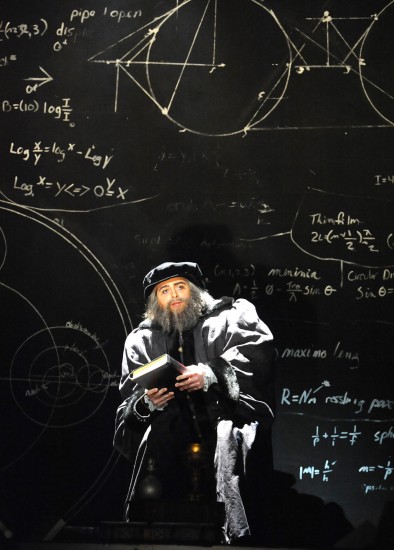

Gounod set the scene in the sixteenth century and called Faust a philosopher since his field was all knowledge. “Knowledge” at that time included alchemy and astrology; it did not include things like microbiology or atomic physics.

Two years ago I saw the San Francisco Opera’s production in which the opening set was a lab and props included not only books, but beakers, test-tubes, and a cadaver. The MetHD production which I saw last December was set somewhat after World War II, and Faust was an aged atomic physicist feeling guilty over his role in developing the atomic bomb. This Opera San Jose production was set in the 19th century when Gounod wrote it.

At a talk-back session following the performance on Sunday, director Brad Dalton explained that he and set designer Steven C. Kemp had created a minimalist set because he wanted to emphasize the spiritual nature of the story. In my opinion they were eminently successful. Rather than build large structures for the sets, they had a single large panel which constituted the entire back wall. As you can see, it was a most effective way of defining the opening scene as a scientist’s study. As the study scene drew to a close, that panel was raised to the flies and replaced by an appropriate new panel for a seamless transition to the next scene.

The Faust legend is based on the literal existence of the Devil, of angels, of meaningful curses, and of Heaven and Hell. When Dalton used the word “spiritual”, he meant that he wanted to emphasize that literalness. In my other life – the one where I am not attending or writing about an opera – I do not believe in love-at-first-sight, unrequited love, the efficacy of prayer or curses, a personal omnipotent God, or any form of after-life. But when I enter a theater, I suspend my disbelief. Some such suspension is a necessity for almost all Grand Opera, Faust requires more than the average, and this production probably takes a bit more than most of the other productions I have seen. So, if you either believe or are good at suspending disbelief, and if you live anywhere near San Jose, I strongly recommend buying a ticket right now for one of the remaining performances from now through May 6.

The final scene offers even more scope for individual directors. Marguerite is in prison sentenced to be hanged. She has had her baby, lost her sanity, and killed the baby. Faust and MÉphistophÉlès arrive with arrangements to rescue her. She refuses the Devil and pleads Heaven for forgiveness. MÉphistophÉlès says she is accursed and will go to Hell, but a chorus of angels says, “No, she is saved” – an outcome which is clearly indicated by the music.

All that is a “given”, but neither the words nor the music indicate what happens to Faust or MÉphistophÉlès, nor does it prescribe what kind of staging to use. Most of the endings I have seen show MÉphistophÉlès either slinking off to the wings, heading down through a trap door into Hell, with or without flames. Sometimes Faust goes with him; other productions leave him lying on the prison floor. Marguerite is usually shown rising from her death and ascending to heaven – the obvious interpretation being that the soprano now symbolizes her soul, not her mortal flesh.

I particularly liked director Jose Maria Condemi’s approach for San Francisco Opera. At the beginning of the scene the long flight of harsh stone dimly-lighted steps emphasized the fact that the prison was a deep dungeon. When the angels sang that Marguerite was saved and she started up the stairs, the light became brighter and brighter – and brighter still until it was blinding and Marguerite had disappeared into it and become one with it.

Other productions have indicated a celestial ladder descending from Heaven, sometimes with an angel or two to accompany Marguerite on her celestial climb. A production I saw about 10 years ago actually had a platform at the top of the stairs where Valentin (of all people) was waiting for her.

You might think that Gounod had given the director enough scope by now, but some directors are greedy, and add a short Epilogue to show us what happened to Faust. In 2004 David McVicar directed a star-studded (Angela Gheorghiu as Marguerite, Vittorio Grigolo as Faust, RenÉ Pape as MÉphistophÉlès, and Dmitri Hvorostovsky as Valentin) cast; he ended the opera with Faust back in his study as an old man dying from the poison he had just taken – the whole beautiful opera had been only a dream. Condemi managed to neutralize his “brilliant” SFO ending by having MÉphistophÉlès come back to Faust and give him back the deed to his soul.

Apparently it’s a tradition for directors to keep their signature ends a secret from the audience, and I have no intention of giving away Brad Dalton’s secrets. Yes, he had two of them, and I heartily approve of both. I’ll close by giving you an obscure hint about one of them. When you get to your seat in the California Theatre (you ARE going, aren’t you?), open the program to the cast list and read the last line:

Supernumeraries Jesigga Sigordardottir

Keep an eye out for this young lady. Gounod doesn’t know about her – she’s all Dalton’s idea. She neither speaks nor sings, but at the final curtain she receives a well-deserved round of applause.

CAST**

Faust

MÉphistophÉlès

Marguerite

Valentin

Marthe

SiÉbel

Wagner

Michael Dailey

Silas Elash

Jouvanca Jean Baptiste

Evan Brummel

Heather Clemens

Betany Coffland

Sepp Hammer

Alexander Boyer

Branch Fields

Jasmina Halimic

Krassen Karagiozov

Tori Grayum

Cathleen Candia

Jo Vincent Parks

2149 Paragon Drive

San Jose CA 95131-1312

408-437-4450

345 South First Street

Betw San Carlos & San Salvador

Downtown San Jose

Photos (except as indicated) by P. Kirk

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on April 28, 2012.