The lights dim. Applause begins near the front of the theatre and rapidly spreads. Conductor Lawrence Renes must be approaching the podium. Sure enough, a distant head is glimpsed from our side seats in row T as he mounts and bows to the audience. All is quiet as he turns to the orchestra and raises his arms.

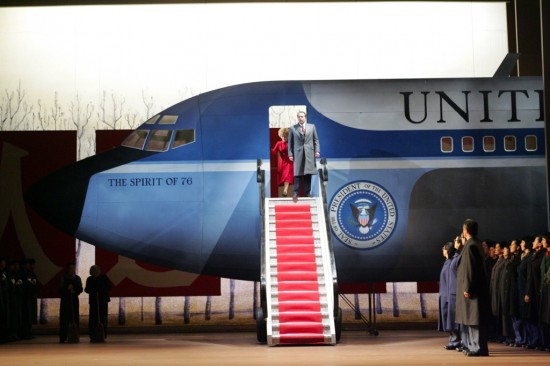

The music begins. Softly. Seductively. An insistent repetitive beat that never leaves us during most of the next three hours. While the overture pours into our ears, our eyes see the heavy outer curtain lift to reveal a screen-scrim filled with a moving vision of a cloudy pre-dawn sky. A dim shape in the sky appears. We draw closer to it; the clouds thin and we see that it is the plane Air Force One, every one of its windows shuttered against the night. A bit closer, then one window lights up and we see Richard Nixon staring into space, thinking about his imminent history-making meeting coming up in a few hours.

The light goes out, and Air Force One drifts off, disappearing in the cloud cover. The screen-scrim lifts a few feet in the air revealing a crowd of people waiting at the airport for the plane to come in. As the music reaches a climax, an image of the plane hurtles across the screen from left to right, touching down for its landing and rapidly disappearing in the mist.

A few bars later the plane, having invisibly slowed down and circled around the rear of the airfield, reappears coming directly toward us. Just as the image of the plane’s nose appears to reach the very front of the stage there is a bit of legerdemain. The image on the front screen-scrim is replaced by an image on a rear screen, and the scrim is whisked away revealing a real 3-D structure, as shown above. Clearly the nose and the steps are real 3-D and the slightly clouded sky is a screen image. The matching of real and image is so well done, that it is not clear in which category to place the wing and motor of the plane. The whole overture bit was technical wizardry at its best, consistent with the music and greatly enhancing it.

Nixon appears, descends the steps, and waves to the crowd in a typical Nixon gesture – the historic visit is officially under way.

MetHD performance February 2011; Janis Kelly as Pat Nixon and James Maddalena as Richard Nixon; photo by Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

This San Francisco Opera performance is the second production of Nixon in China that I have seen. Last year I saw and reviewed the MetHD performance with James Maddalena and Janis Kelly as Richard and Pat Nixon. Since that review included a fairly detailed synopsis of the opera, you might want to read it now. Anyhow, from here on I will assume that you know what the story IS, and will write some of impressions of HOW it is told.

In almost all classical grand opera, emotion is a vital component. I judge the performance of a singer by his or her ability to portray that emotion by tone of voice, facial expression, and body language. But here the actors are portraying real people in a tense situation. They have the impossible job of showing a character’s emotion to the audience while concealing it from their fellow-actors! Further they have to do this entirely by sound and body language, since most of the audience is too far away to read their faces. It’s not surprising that the MetHD came closer to this goal, since we saw lots of close-up views.

Overall I felt that the Met production concentrated more on the people and made them seem more real. I can’t pin down all of the reasons I feel this way, but basically I think that Director Michael Cavanaugh and Set Designer Erhard Rom paid too much attention to the physical setting in San Francisco whereas in New York Peter Sellars and Set Designer Adrianne Lobel kept the setting as simple as possible so as not to distract from the tension between the characters.

Consider, for example the formal banquet, which occurred at the end of the first day. Picture A above is a news photo of the actual event in 1972. It was taken from the back of the hall and Nixon and Chou are barely visible on the stage facing the camera. As a picture it is historically accurate, but it can hardly be called a dramatic photograph.

The Met production (Picture B) changed the scene to a more familiar banquet situation with tables. The simple display of two flags on the back wall was true to history, but the total scene was much more spacious and focused on Chou and Nixon standing to give toasts – exactly what the music and libretto said they were doing.

SFOpera (Picture C) also has the banquet tables but the scene is dominated by the massive red podium and a garish back wall featuring an enormous Chinese flag superposed over an even larger montage of slightly impressionistic American flags. Viewed simply as a pair of pictures or stage sets, there’s no question but that C is more dramatic than B. However, sitting in the audience the visual part of my mind is trying to discern meaning in the particular montage of the flags; and Nixon is dwarfed by the podium upon which he stands. Neither the flags nor the podium are referred to in the words and the music – my eyes and my ears are telling me different things. Not good.

Fast-forward to Act III. The conference is over. Final toasts have been drunk. Last goodbyes have been said. The Americans have returned to their hotel and the Chinese to their homes. Adams and Goodman have postulated they are each winding down from 5 tension-filled days; the Nixons, Kissinger, Chou, and the Maos are visited in turn, each giving us, the audience, their innermost thoughts. How do you stage such a scene?

Here, director Erhard Rom borrowed an ancient Greek theater device known as periaktoi – moveable triangular columns to divide the stage into varying sub-stages. Except for the columns, a few pure red chairs and tables, and a pure black backdrop with seemingly random red lines, the stage was featureless. As focus in the music shifted from one character to another, the columns and furniture were moved to new positions. All very dramatic in itself – but no apparent relation to the words or music.

MetHD performance February 2011; Janis Kelly as Pat Nixon and James Maddalena as Richard Nixon; photo by Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera.

On the other hand, the Met placed the action in a dream-like setting in which the Great Hall became a dormitory with simple cots for each of the main characters. On the surface a single room, but with unseen boundaries completely isolating each of the units.

Well! More than enough criticism. Despite my feelings about the sets, I enjoyed the performance overall. Indeed, if it were having a longer run, both Sara and I would be tempted to go again. But it closes on July 3. For detailed information and to buy tickets go to San Francisco Summer 2012

San Francisco Opera

301 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94102

(415) 861-4008

sfopera.com

Except as noted, all photos by Cory Weaver, San Francisco Opera

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on June 30, 2012.