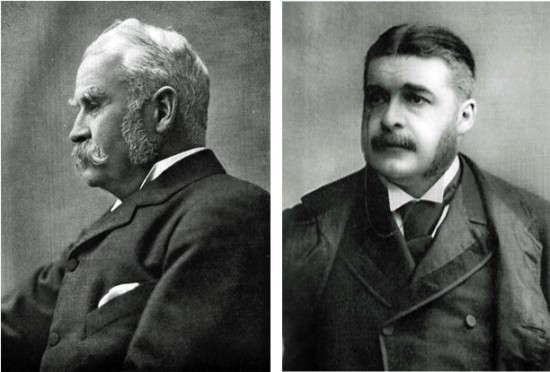

William S. Gilbert (librettist) and Arthur Sullivan wrote 14 operas together in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The middle nine (in order of composition) beginning with Pinafore in 1878 and concluding with The Gondoliers in 1889 are still performed more or less frequently by amateur, community, and professional companies throughout the English-speaking world.

Critics generally consider¬†Pinafore,¬†The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado¬†to be the “big three” of the¬†G & S repertoire, but personally I would have to make it a “big six” by including¬†Iolanthe,¬†The Yeomen of the Guard, and¬†The Gondoliers, all six in no particular order. And the other three:¬†Patience, Princess Ida, and¬†Ruddigore¬†– aren’t far behind. I saw all of them as a teenager way back in the 1930s when the¬†D’Oyly-Carte Opera Company visited New York City with a nine-week stand; I’ve seen most of them here in the Bay Area in the past decade; and many of them umpteen times in between.

The last two operas showed that genius is finite. If someone had never seen a¬†G&S¬†opera before, they would probably be mildly amused, but compared to the “big nine” the plots seem a bit tired, the words not quite as clever. I’ll still go to see¬†The Grand Duke or Utopia Limited¬†when I get a chance, but it will be for historical completion rather than with a sense of keen anticipation.

Their first opera,¬†Thespis, was hastily written as a “Christmas entertainment” in 1871. It was reasonably successful, but the music was never published and no copy is to be found. Judging from critics writing at the time, it was more closely related to Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld and La belle H…lŤne, than to any of the other¬†G&S.

Audiences in those days had more stamina than we do today. When they went to the theater for an evening they wanted more than an entr…e of a full-length opera; they also wanted an appetizer and/or a dessert. In 1874¬†Richard D’Oyly Carte¬†was producing Offenbach’s¬†La P…richole, and needed an “afterpiece”. The result was¬†G & S’s only 1-act opera,¬†Trial by Jury. It was a tremendous success, but as a short one-act production is in a different category and can’t really be compared with their full-length operas.

And so, at long last, we come to the subject of today’s essay:

The Lamplighters’

production of

The Sorcerer

by

W. S. Gilbert and A. S. Sullivan

2:00 PM, Sunday, March 23, 2013

Herbst Theatre

San Francisco, CA

Having just seen this performance, I’d have to agree that¬†The Sorcerer is not quite in the same class as the “big nine”, but it’s darn close. The plot is no more improbable than many of the others, the words show typical¬†Gilbert¬†cleverness, and¬†Sullivan’s music is delightful. Gilbert’s “gimmick” for turning chaos into a happy ending isn’t as clever as Buttercup’s admission that she had mixed up two babies: “The well born babe was Ralph – your captain was the other!” Or Ruth’s plea that the pirates: “are no members of the common throng; they are all noblemen who have gone wrong.” But it does the trick.

Years ago in a television interview I heard¬†Beverly Sills¬†say that any attempt to “improve” or parody¬†G&S was doomed to failure. The parody, the satire, the humor are all in¬†Gilbert’s libretto – change anything and you risk losing all the original appeal. Director¬†Jane Hammett¬†does not fall into that trap anywhere in the opera itself, but she does go all out to “improve” the overture by filling the stage with a mimed vignette purporting to show what goes on back-stage just before the opening curtain at a provincial touring company performance from the 1870s. Personally, I found it distracting from the music, but I have to give Hammett¬†and the¬†Lamplighters¬†A for effort. The stage was totally soundless, but the supertitle screen carried a lively dialog. Also, the program had an insert purporting to be the program for this prologue performance, and including ads for such products as “The Pansy Corset” and “Bovril”.

Action takes place in the small village of Ploverleigh, England, on a pleasant summer day late in the 18th¬†century: Act 1 at noon, Act 2 at midnight. The cast of nine is headed by the young lovers:¬†Robert Vann as Alexis and¬†Lindsay Thompson Roush¬†as Aline. Not only are they in love, but their parents thoroughly approve the match. I’ve seen both of them in several lead roles recently, but this is the first time I’ve seen them together. Not only are their voices a delight in solos, but they blend well together in their duets.

Alexis’ widowed father, Sir Marmaduke (Robby Stafford), is delighted with the marriage because Aline’s family is wealthy. However he cautions his son not to be so demonstrative in public – it simply isn’t done in our elevated social class. Aline’s mother Lady Sangazure (Megan Stetson), long a widow, approves because it’s a big step up the social ladder for her daughter. Each of the two parents delivers an aside to the audience that they have a romantic yen for the other, but it would be such bad taste to admit this to anyone they know, particularly to the other.

Robby Stafford as Sir Marmaduke, Robert Vann as Alexis, James MacIlvaine as the notary, Lindsay Thompson Roush as Aline and Megan Stetson as Lady Sangazure

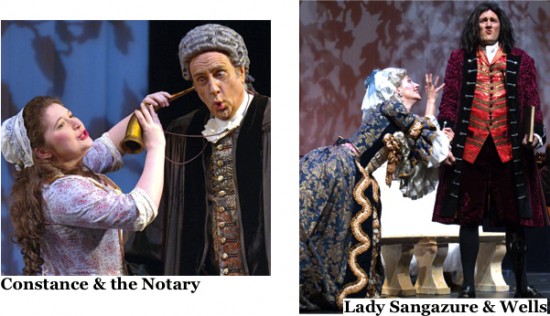

The young lovers embrace on every possible occasion to the dismay of their parents, and all are agreed that the sooner they get married the better. A Notary (James MacIlvaine) is summoned and in no time at all the deed is done.

But not everyone has such a happy love life. Constance (Rose Frazier) confessed to her mother, Mrs. Partlet (Kelly Powers) that she was in love with the Vicar, Dr. Daly (Baker Peeples), but that he apparently showed no interest in her. Dr. Daly is getting on in years, but muses in a lovely ballad,

Time was when Love and I were well acquainted.

Time was when we walked ever hand in hand

A saintly youth, with worldly thought untainted,

None better-loved than I in all the land!

Time was, when maidens of the noblest station,

Forsaking even military men,

Would gaze upon me, rapt in adoration–

Ah me, I was a fair young curate then!

Although¬†Baker Peeples¬†has sung in almost every¬†G&S¬†opera over the years, this is the first time I have heard him. But he has usually been on the¬†Lamplighters’ program as Music Director. His voice is still good and he’s an excellent actor.

The Widow Partlet pleads Constance’s case to Dr. Daly with extremely broad hints about marriage. He claims it’s too late – “I shall live and die a solitary old bachelor.” However, he murmurs an aside to the audience as he gazes at Constance, “Be still my fluttering heart.” During the dialogue between the mother and the clergyman, it was fascinating to watch Constance’s face and body language register embarrassment at the widow’s forwardness, hope, and sadness – rapidly changing as the conversation seemed to imply different outcomes.

At this point we seem to be headed rapidly to a pleasant one-act curtain-raiser. The wedding party becomes the Finale, and during the joyous celebration everyone relaxes enough to declare his or her love. Sir Marmaduke and Lady Sangazure fall into each other’s arms; likewise Constance and Dr. Daly. Maybe Mrs. Partlet and the Notary will make it unanimous.

B U T

That’s not what happens. Alexis won’t leave well enough alone. He wants all the unmarried people in the village to fall in love and be as happy as he is. He summons the title character of the opera who immediately introduces himself in an authentic-sounding cockney voice.

Oh! my name is John Wellington Wells,

I’m a dealer in magic and spells,

In blessings and curses

And ever-filled purses,

In prophecies, witches, and knells.

If you want a proud foe to “make tracks” –

If you’d melt a rich uncle in wax –

You’ve but to look in

On the resident Djinn,

Number seventy, Simmery Axe!

It seems that John Wellington Wells¬†(Chris Uzelac) has a Love Philtre that will make people fall instantaneously, irrevocably, and eternally in love. Alexis asks him about it and he responds,¬†“Sir, it is our leading article.” Alexis is immediately sold and says, in effect, “Let’s do it. We’ll spike the tea at our wedding party, then everyone in the village can be as happily in love as we are.” Wells, as a good businessman, agrees with his customer and answers his questions:

ALEXIS And how soon does it take effect?

WELLS In twelve hours. Whoever drinks of it loses consciousness for that period, and on waking falls in love, as a matter of course, with the first lady he meets who has also tasted it, and his affection is at once returned. One trial will prove the fact.

ALEXIS Good: then, Mr. Wells, I shall feel obliged if you will at once pour as much philtre into this teapot as will suffice to affect the whole village.

ALINE But bless me, Alexis, many of the villages are married people!

WELLS Madam, this philtre is compounded on the strictest principles. On married people it has no effect whatever. But are you quite sure that you have nerve enough to carry you through the fearful ordeal?

ALEXIS In the good cause I fear nothing.

WELLS Very good, then, we will proceed at once to the incantation.

Wells’ dialogue and patter song are all delivered in extreme Cockney. After the show I asked¬†Chris Uzelac¬†how he had achieved that perfection. He responded with a startling lack of accent, “About four months of very hard work.”

And we come to the Finale of Act I. Dire spirits are summoned to give the philtre its magical power, the tea is brewed, the philtre added, the villagers and dramatis personae come in dancing and singing, the tea is poured and passed around to more dancing and singing, the theatre begins to darken, the characters begin to rub their eyes and stagger about the stage as the chorus sings their final verse:

Oh, marvellous illusion!

Oh, terrible surprise!

What is this strange confusion

That veils my aching eyes?

I must regain my senses,

Restoring Reason’s law,

Or fearful inferences

Society will draw!

They fall insensible on the stage as the lights black out to end Act I.

The discerning reader will have noted that there is a certain element of chance in Wells’ description of how the philtre works. A man falls in love with the first unmarried woman he sees – and that might not be the same woman he was courting a mere 12 hours before. Perhaps then it is not surprising in Act II¬†

All Hell breaks loose!

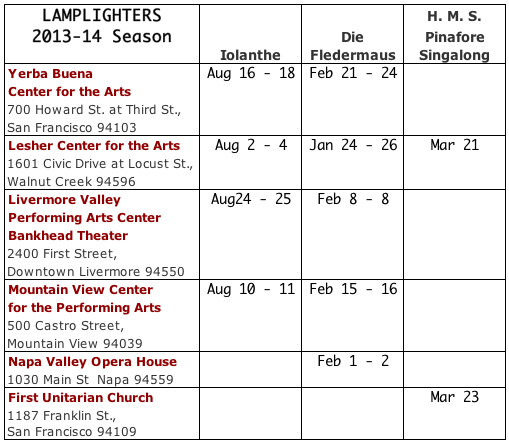

Time to go. See you next year? It’s an interesting program:¬†

Photos are by Lucas Buxman unless stated otherwise

All quotes are from The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Complete Plays of Gilbert and Sullivan, by William Schwenk Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on March 28, 2013.