In her pre-opera talk on October 28, 2013,¬†Desir…e Mays¬†referred to¬†The Flying Dutchman¬†as¬†Wagner-Lite. Since I regard “Lite Beer” as an abomination, I don’t entirely like her term – I’d rather call it¬†Wagner-Accessible or¬†Wagner-User-Friendly. The music is still powerful, but I walk away with a couple of actual melodies running through my head; whereas I walk away from a performance of¬†The Ring¬†thoroughly awed by the cumulative effect and a head full of motifs fighting for my attention.¬†

The plot of¬†Wagner’s opera¬†The Flying Dutchman¬†is based on an ancient legend:

Several centuries ago a sailing ship trying to sail around¬†The Cape of Good Hope encountered a violent storm and could make no progress. Rather than ride out the storm or flee before it, the skipper, a stubborn Dutchman, kept fighting it vowing aloud, “I’ll make it around this blasted cape if I have to sail until Doomsday.”

Satan heard his shouts into the gale: “Your wish is granted. You shall sail until Doomsday and never again touch land. We got ourselves a deal.”

An angel overheard this and insisted the contract was not valid without an escape clause, so the curse was amended to allow him to go ashore once every seven years and search for a wife.

If he could wed one who was pure and virtuous and would be faithful to him unto death, his curse would be removed.

“Impossible,” you snort. “A ridiculous story, even by operatic standards. I don’t believe it!” You’re missing the point. No one asks you to believe it. It’s a legend. The legend exists whether or not its story is real. Take it from there.

And Richard Wagner took it from there with his brilliant music and libretto. He condenses the entire story into a single day Рa-once-in-seven-years day Рwhen the Dutchman goes ashore in search of his ideal wife.

I was even more impressed by the¬†San Francisco¬†Opera’s production as a whole than I was by any particular feature of it. Don’t arrive late, because the excitement begins when Maestro¬†Patrick Summer brings down his baton for the first note of the rousing overture.

It grows when the curtain rises to show the deck of a ship and the overture merges seamlessly into Act I of the opera. We see the deck of a Norwegian ship and hear the magnificent voices of the sailors as they secure the ship, now safely at anchor in a Norwegian fjord. If you ask me for my favorite singer in this production, despite the fine performances by the six soloists, I would choose the collective voices and actions of the men’s chorus.

Daland (Kristinn Sigmundsson) appears on deck and comments (in a resonant bass voice) on the irony of having to seek shelter in a fjord only 7 miles from his home port. He bids the Steersman (A. J. Glueckert) keep watch, then accompanies the crew below for some well-earned rest.

The Steersman sings a pleasant but inconsequential little ditty about his girl. After a couple of verses in his fine tenor voice he bores even himself and drops off to sleep. He is not awakened as another ship with red sails drops anchor beside him.

The scene changes in a most ingenious fashion. With no break in the music, a large portion of the stage floor swings open almost to the vertical as if it were a trap door, its undersurface depicting a ghostly semi-ruin of a ship, festooned with dripping dust and cobwebs. A platform rises from below, bringing the Dutchman (Greer Grimsley) up to stage level. The entire stage is bathed in an eerie red light – (a technique used through-out the opera to indicate the¬†Flying Dutchman). The total effect gives the vivid impression that we are now on “the ship from Hell” – an impression further enforced by Wagner’s music.

The Dutchman sings with fervor about his curse and how this is his one day ashore. He is hopeful that this time he’ll find his ideal wife, but philosophic that he probably never will.

He leaves to go ashore, the trapdoor closes, and we are back on the Norwegian ship. Daland comes on deck, sees the stranger on the shore, and invites him aboard where they engage in my favorite sub-genre of opera, the male duet. Grimsley’s strong bass-baritone blends perfectly with Sigmundsson’s deep bass as they introduce themselves to each other. Then comes one of the fastest marriage negotiations in opera:

Dutchman: Do you have a daughter?

Daland: Yes. Here’s her picture.

Dutchman: Is she virtuous?

Daland: Very.

Dutchman: May I marry her? You can have all the treasures in my ship.

Daland: It’s a deal.

Well, there are a few more words, and of course it takes longer to sing them, but still it’s a bit of a whirlwind.

The weather has turned fair, the Dutchman goes back to the¬†Flying Dutchman, and it’s “Hurrah for the Homeward Bound” as we sail into Act II.

The act opens in the hall of Daland’s house where Senta’s nurse Mary (Erin Johnson) is trying to organize the spinning of a group of local girls. She displays no great interest in the job and has little success – they would rather sing their catchy little spinning song.

Mary urges Senta (Lise Lindstrom) to join the other girls spinning – but Senta is engrossed in her painting of the Dutchman (whom she knows only through his legend). Finally she agrees, but only if the girls “have done with your stupid song, your whirring and whirling wearies my ears.” She asks Mary to sing the¬†Ballad of the Flying Dutchman. “No way,” says Mary; “I should never have sung it to you in the first place.”

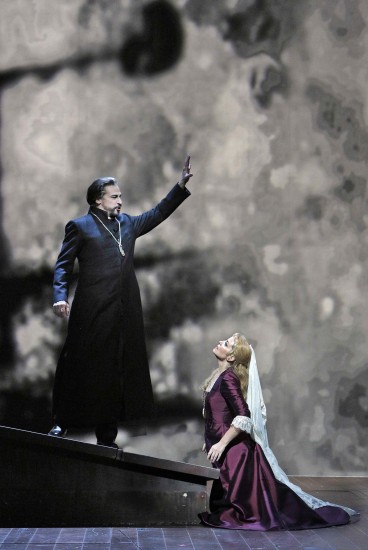

“Very well,” says Senta; “I’ll sing it myself.” Which she does with tremendous passion and feeling – in both actions and voice. She sinks to her knees in emotional exhaustion – then springs up again crying,

Let me be the one whose loyalty shall save you!

May God’s angel reveal me to you!

Through me shall you attain redemption!

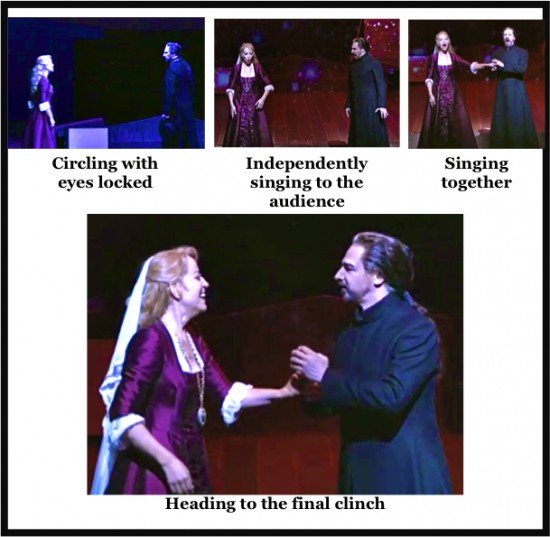

Final scene of Act II. Senta alone on stage. Two captains enter. Senta and the Dutchman lock eyes. Daland is ignored.

Daland: “Daughter, meet your husband. I am rich beyond imagination”

Senta: “Can I believe my eyes? He is the man of my dreams. Can I save him from his terrible fate?”

Dutchman: “Can I believe my eyes? Can this gorgeous woman redeem me from my terrible fate?

Daland leaves them alone to “get acquainted.” They continue to circle as if in a trance – sometimes to the orchestra only – sometimes one or the other singing to the audience. They close in on each other. They touch hands – tentative at first – then passionately. They sing together in joy. They clinch¬†. . .¬†Happy ending to Act II.

Act III begins immediately with no pause in the music and a scenery shift to the deck of the Norwegian ship where a party celebrating Senta’s marriage is in progress. The crew spots the ghost ship off-stage (actually on the 2nd¬†floor where they sing with amplification) and invite their crew to join them. There is some fascinating back and forth between the two ships. We only see the Norwegian ship, but when the crew of the¬†Flying Dutchman¬†is singing, the whole stage becomes lit with eerie red – appropriate to the unworldly music – and reverts to normal lighting when the locals are singing. Very dramatic.

The final scene of the opera is made up of four episodes. First, Erik (Ian Storey), a local huntsman who is in love with Senta, urges her to forget this romantic nonsense with a mysterious stranger and marry him. He reminds her that last summer she seemed to return his love and they actually had a smooch or two. Senta repulses him, but damage has been done.

The Dutchman has over-heard enough to conclude that Senta does not come pure to him and therefore does not meet the requirements of the escape clause. [This would be ridiculous in the 21st century, but the legend is set many centuries ago when morals were stricter and the first kiss took place after the engagement – or even after the marriage]. He is doomed and can only look forward to Judgment Day for release. He ignores her pleas, sings an agonizing, “Den: Fliegenden Hollander nennt man mich” (The Flying Dutchman I am called) and boards his ship.

Mary, Erik, and Daland rush on stage singing, “Senta, Senta, art thou raving?” She ignores them, sings her final words (freely translated from the German)

Be cheerful thy mind, be joyous thy heart!

Thine will I be until death shall us part:

and flings herself into the sea.

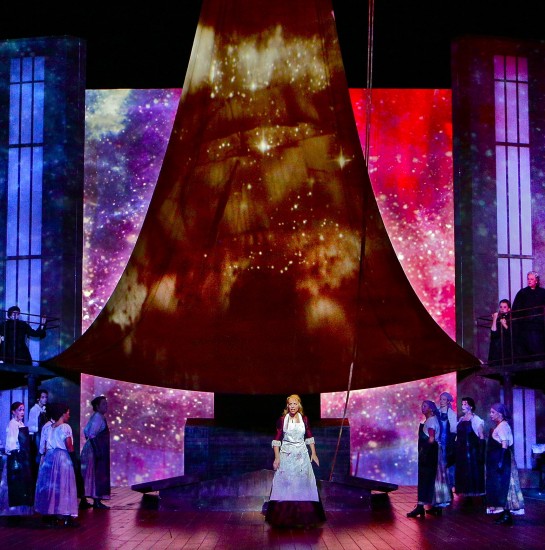

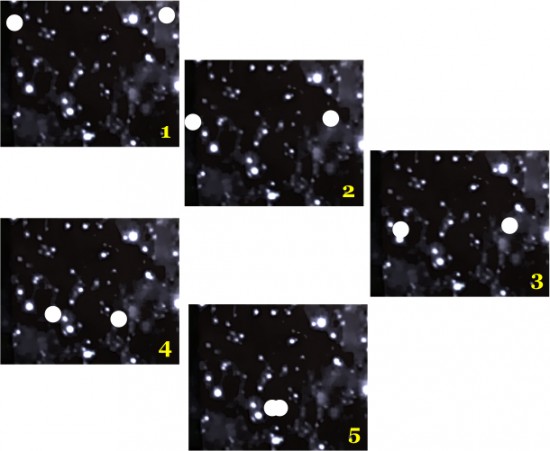

The final stage directions in¬†Wagner’s Libretto call for Senta to “Cast herself into the sea,” for the¬†Flying Dutchman¬†to sink, and for “the forms of Senta and the Dutchman, embracing each other to rise from the sea and float upwards.” I was curious how this modern high-tech performance would handle the supernatural phenomenon – and they did it subtly and beautifully. As Senta leaps to her death the skies on the background screens change from the stormy maelstroms during the Dutchman’s departure to a clear starry night, in perfect unison with the music’s changing from violent to sublime. I noticed that two stars were brighter than any of the others and that they were moving towards each other; as the orchestra played its final ethereal chord the two stars were united for all eternity.

Still four more performances left in November. Come see for yourself.

| PERFORMANCES |

| Tue 10/22/13 8:00 pm |

| Sat 10/26/13 8:00 pm |

| Thu 10/31/13 7:30pm |

| Sun 11/3/13 2:00 pm |

| Thu 11/7/13 7:30pm |

| Tue 11/12/13 7:30pm |

| Fri 11/15/13 8:00pm |

San Francisco Opera

301 Van Ness Avenue

San Francisco, CA 94102

(415) 861-4008

sfopera.com

Except as noted, all photos by Cory Weaver, San Francisco Opera;

Video clips courtesy San Francisco Opera

Cropping and arrangements by Philip Hodge

Quotes in¬†Italics¬†are from the¬†Project Gutenberg eBook of¬†Der Fliegende Hollť§nder

CAST

| THE DUTCHMAN | GREER GRIMSLEY |

| SENTA | LISE LINDSTROM * |

| ERIK | IAN STOREY |

| DALAND | KRISTINN SIGMUNDSSON |

| STEERSMAN | A.J. GLUECKERT |

| MARY | ERIN JOHNSON |

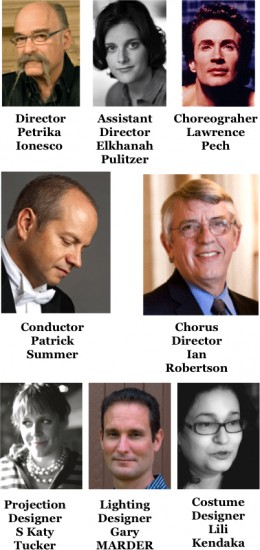

PRODUCTION CREDITS

| CONDUCTOR | PATRICK SUMMERS |

| DIRECTOR, SET DESIGNER | PETRIKA IONESCO |

| COSTUME DESIGNER | LILI KENDAKA |

| LIGHTING DESIGNER | GARY MARDER * |

| PROJECTION DESIGNER | S. KATY TUCKER |

| CHORUS DIRECTOR | IAN ROBERTSON |

| CHOREOGRAPHER | LAWRENCE PECH |

* SAN FRANCISCO OPERA DEBUT

This review by Philip G Hodge appeared in sanfranciscosplash.com on November 1, 2013.